Editor’s Note: For its fourth post, RealForecasts.com is re-publishing a white paper titled “Never Quit in the Middle of a Dip”, which was written in February of 2009. Whether you were in a Trap, on a Cliff or in a Dip during the last downturn — and whether you stuck or quit — this post can still help you to better prepare yourself for the inevitable next downturn.

Never Quit in the Middle of a Dip

Jeffrey J. Peshut

February, 2009

As the current real estate downturn continues, many real estate investors will feel pressure to divest themselves of their existing properties and portfolios — and even of the real estate asset class as a whole — to avoid further losses and pursue alternative investments that they perceive will provide superior risk-adjusted returns in the future. This pressure is sure to intensify the longer the real estate downturn lasts and will likely reach its peak at about the same time as the real estate market reaches its cyclical trough. This could lead many investors to sell at precisely the wrong time, locking in significant capital losses from which they may never recover.

This article suggests that real estate investors should never quit in the middle of a downturn or “dip”. Instead, they should ignore sunk costs, evaluate their investments prospectively and stick with the investment until the market recovers and they are once again in a position to enjoy the returns that investing in real estate is expected to provide over time.

When to Quit and When to Stick

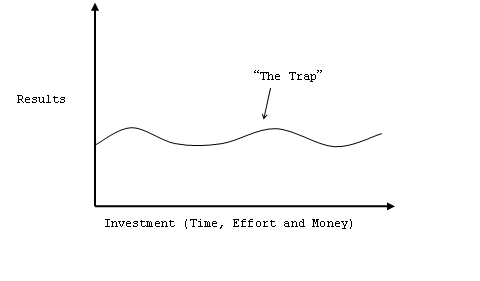

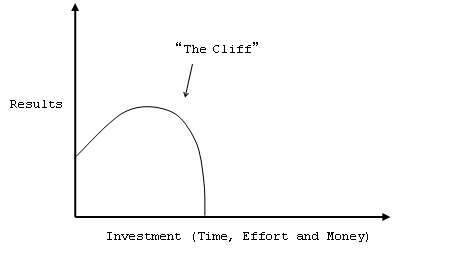

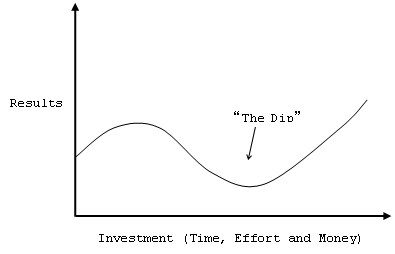

Three curves help to both illustrate the types of situations that lead people to quit and explain why it is important to quit in some situations but stick it out in others. These three curves are “The Trap”, “The Cliff” and “The Dip”.

The Trap: “The Trap” describes situations in which we keep investing time, effort – and money – but nothing changes very much. Despite our best efforts, the situation doesn’t get much better and it doesn’t get much worse. It looks something like this:

An example of The Trap in real estate investing is a property at which the increases in operating expenses and capital expenditures absorb most of the growth in rental rates. As a result, there is little if any capital appreciation at the property. Under a worse-case scenario, increases in operating expenses and capital expenditures exceed the growth in rental rates and the value of the property declines over time. Some have even referred to this type of property as a “value trap”.

The key to dealing with The Trap is first to recognize that we’re in one and then to get out of it as quickly as is reasonably possible. The opportunity cost of sticking with a situation that is unlikely to get better is too high.

The Cliff: “The Cliff” describes situations that involve a high degree of risk and a high cost of failure. At first, we get the results we want. Then, before we recognize it, we find ourselves staring into the abyss, with limited options to quit. As its name implies, it looks something like this:

An example of The Cliff in real estate investing is a highly-leveraged property or portfolio that faces some type of default situation – whether a payment default, technical default (e.g., breach of a DSCR covenant) or term default. The default situation leads to either a forced sale at discounted pricing, a deed-in-lieu of foreclosure or a foreclosure. The ultimate result is a loss of most — and usually all — of the invested capital.

The key to dealing with The Cliff is similar to the key to dealing with The Trap – we need to recognize that we’re headed for one and – if it’s not too late – quit as quickly as is reasonably possible. Of course, the potential cost of staying on The Cliff is much greater than staying in The Trap. The potential cost of staying in The Trap is losing other opportunities. The potential cost of staying on The Cliff is losing our entire investment.

The Dip: “The Dip” describes situations in which our initial investment of time, energy and money provides the results we were expecting – often quickly and easily. Then, after a time, the expected results begin to wane. For those willing and able to push a little bit longer and a little bit harder than the rest, however, we not only find ourselves achieving the results we first expected, but extraordinary results well beyond that. (Extraordinary results also accrue to those who quit early and refocus their time and effort elsewhere, but that’s a separate topic for a separate discussion.)

Almost every situation in which it is worth investing our time, effort and money is illustrated by “The Dip”. We experience The Dip in school, in sports, in our relationships, in our careers and in our investing. See The Dip (New York: Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 2007). It looks something like this:

The Dip is so prevalent because most of the competitive systems we encounter are set up to encourage the many people who start to quit for the benefit of the few that stick it out. These systems are set up to “shake out the weak hands”. Quitting creates scarcity and scarcity creates value for the few that stick it out.

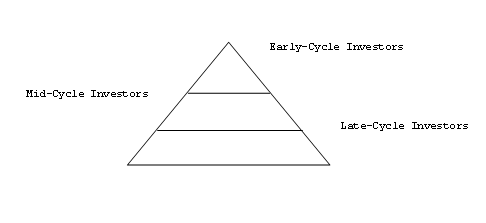

In effect, The Dip and these competitive systems are based upon various types of pyramid structures. As the Bernie Madoff situation reminds us, a pyramid structure is often a scam in which many people at the bottom support a few at the top. But a pyramid structure is not always a scam. In fact, we encounter it a lot more often than we realize.

For example, most private clubs are based upon a type of pyramid structure. Many people sign up for health clubs but very few use the club frequently after they join. This allows the operator to build a smaller facility and keep rates reasonable. The many members who join, but quit using it, support the few who join and do.

Similarly, NetFlix allows its customers to rent an unlimited number of DVDs each month for $8.99 per month, which includes postage. If someone watched a movie the day it came in and sent it right back, they’d get to watch at least six movies each month. Of course, for every customer that watches six, there are many more people who watch one movie — or even no movies — each month. Again, the many members who join but quit using it support the few who join and continue to use it.

Investment markets are also based upon a type of pyramid structure. Those who sell or quit during The Dip support those who invest during The Dip by providing them with the opportunity to enter the market at discounted pricing. The many who invest late in a market cycle also support the few who invested during The Dip by driving up values. Not surprisingly, these late-cycle investors are often some of the same investors who sold during the previous Dip. The investment market pyramid structure looks like this:

An example of where we often see The Dip occur in real estate investing is a high-quality property in a prominent location in a first-tier submarket of a first-tier MSA — owned free and clear by a well-capitalized owner — that experiences a downturn in its local real estate market or the loss of a major tenant. Often, the two events occur simultaneously. As a result, the property’s cash flow and value decline. Depending upon the magnitude of the market downturn, it may take significant time, effort and money for the owner to work through The Dip. Ultimately, however, the market and property recover and the property’s cash flow and value begin to increase at an increasing rate, quickly exceeding the highest levels set prior to the downturn.

Having already discussed The Trap and The Cliff, it’s not too difficult to see how those of us experiencing The Dip might be fooled into believing that we are instead experiencing one of the situations that will ultimately lead to failure and, therefore, will feel pressure to give up or quit. Of course, the key to dealing with The Dip is being able to distinguish it from The Trap and The Cliff and then being able to stick with the situation long enough to get through it. If, however, we make the mistake of selling during The Dip, we will lock in our losses and provide the entry point at discounted pricing for one of the next market cycle’s “early” investors.

So it’s really very simple. Quit The Traps and The Cliffs and stick with The Dips. The hard part is distinguishing among the three and having the mental toughness to quit the first two and stick with the third.

Trap, Cliff or Dip?

Several key questions can help us to distinguish The Dip from The Trap or The Cliff:

- What are the long-term population and job growth prospects for this MSA and Submarket? Has the market recovered from similar downturns in the past?

- What is the property’s position within its submarket and competitive set? Is its market position improving or deteriorating? Are there steps we can take to maintain or improve it?

- Do we own the property free and clear or is it subject to debt financing? If subject to debt financing, can we forecast a scenario that will lead to a payment, technical or term default?

- Do we have the capital resources necessary to fund capital expenditures or to restructure the capital stack to head off a potential default?

The better the MSA, the Submarket, the property’s market position and our capital resources, the more likely we are experiencing The Dip and not The Trap or The Cliff.

Sticking With The Dip

It’s human nature to quit when it hurts. Short-term pain has more of an impact on the average person than long-term gains do. The key to sticking with an investment through The Dip is to rise above the short-term pain and stay focused on the long-term gain when others are losing sight of it. We should never quit something with great long-term potential just because we’re having difficulty coping with the discomfort of the moment.

It’s also important to recognize that it’s the difficult challenges – The Dips – that provide us with opportunities to pull ahead of our competitors. In a competitive market environment, adversity is actually our ally. The harder it gets, the better our chances of differentiating ourselves from the competition. If adversity causes us to sell or quit an investment in the middle of The Dip, we’ve not only squandered a great opportunity, we’ve likely passed that opportunity along to one of our competitors.

One technique that will help us to stick with an investment through The Dip is to write down in advance the circumstances under which we will quit — and when. We should then stick with the investment unless these circumstances come to pass. Developing an exit strategy as part of our initial underwriting process will provide us with invaluable perspective if we find ourselves in a painful situation, frustrated or stuck.

Summary

We’ve seen that sticking with The Dip leads to extraordinary results, whereas sticking with The Trap or The Cliff leads to failure. In the case of The Cliff, that failure can be catastrophic. We’ve also discussed ways to recognize whether we’re in The Dip or The Trap, or on The Cliff, and to overcome short-term pain to realize long-term gains by quitting The Traps and The Cliffs and sticking with The Dips. In other words, as the title of this article correctly states, we should never quit in the middle of a Dip.