By Jeffrey J. Peshut

August 18, 2014

In a recent post on LinkedIn, economic strategist Paul Winghart correctly points out that yield curves of Treasury securities have an unrivaled track record of out-forecasting even the best economic forecasters — present company excepted, of course! In support of his proposition, he cites “Forecasting Recessions: The Puzzle of the Enduring Power of the Yield Curve” (Rudebusch and Williams, 2008). Mr. Winghart veers off track, however, when he echoes Keynesians like Fed Chair Janet Yellen and argues that the yield curves’ greatest powers are their ability to capture and reflect the amount of economic slack in the economy at any given moment.

This post will show that yield curves accurately forecast business cycles because they reflect the Fed’s manipulation of both interest rates and the supply of money and credit, not economic slack in the economy. Therefore, Mr. Winghart presented the right chart, but with the wrong reasons for why it works.

This post will then go on to forecast the 10-Year Treasury/3-Month Treasury spread over the next 12 to 24 months and suggest the likely impact the forecasted spread wil have on the economy.

Yield Curves of Treasury Securities and Forecasting Business Cycles

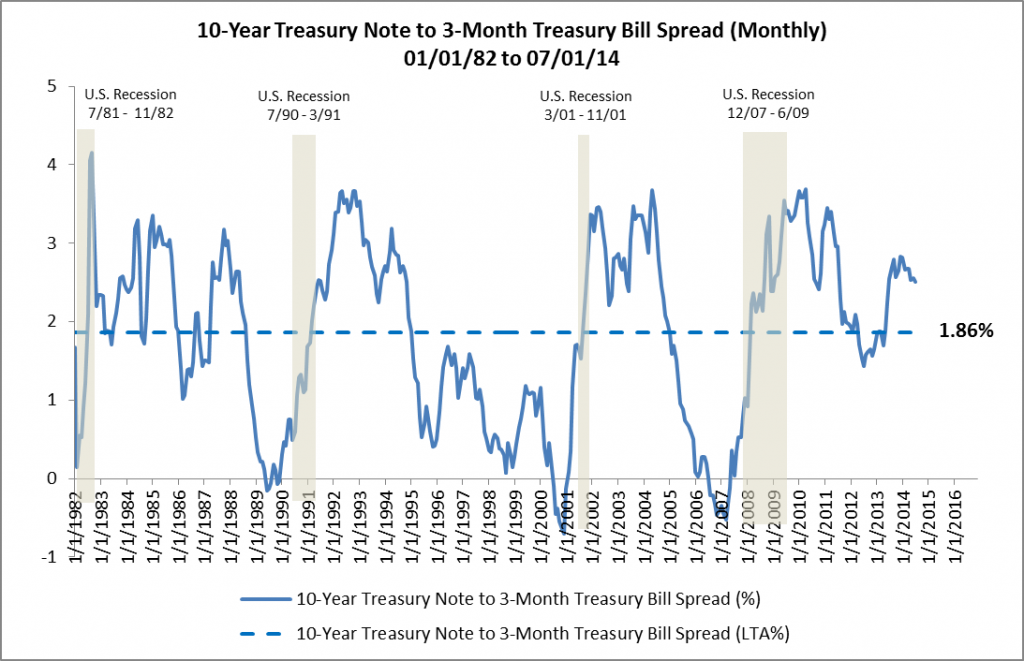

The yield curves of Treasury securities — specifically the spread between yields of long-term and short-term Treasury securities — have a well-documented history of accurately forecasting business cycles in general and economic recessions in particular. A case in point is the spread between the yield on the 10-year Treasury Note and the 3-Month Treasury Bill. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1: 10-Year Treasury Note to 3-Month Treasury Spread 01/01/82 to 07/01/14

Shortly before each of the last four economic recessions, the spread between the 10-Year Treasury Note and the 3-Month Treasury Bill approached zero and in the case of the last three recessions actually fell below zero. Put differently, in each case the yield curve flattened and even inverted. Any investor monitoring the yield curves or this chart could have easily seen the economic downturns far enough ahead to still have time to take the appropriate protective actions.

Why Do They Work So Well?

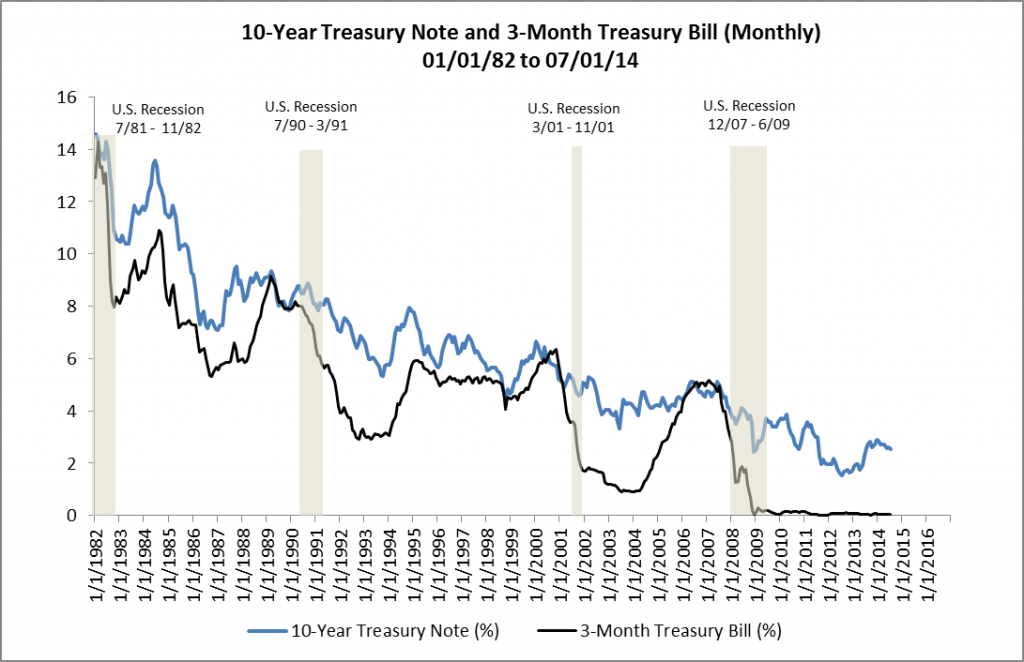

To understand why the yield curves of Treasury securities forecast business cycles so well, it’s necessary to first look at the yields on the long-term and short-term Treasuries side-by-side to see whether one or the other is more responsible for the widening and narrowing of the spreads. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2: 10-Year Treasury Note and 3-Month Treasury Bill 01/01/82 to 07/01/14

You can see right away that, except for the early 1980s, yields on the 3-Month Treasury Bill have been much more volatile than yields on the 10-Year Treasury Note and that they have been much more responsible for changes in the spread than yields on the 10-Year Treasury.

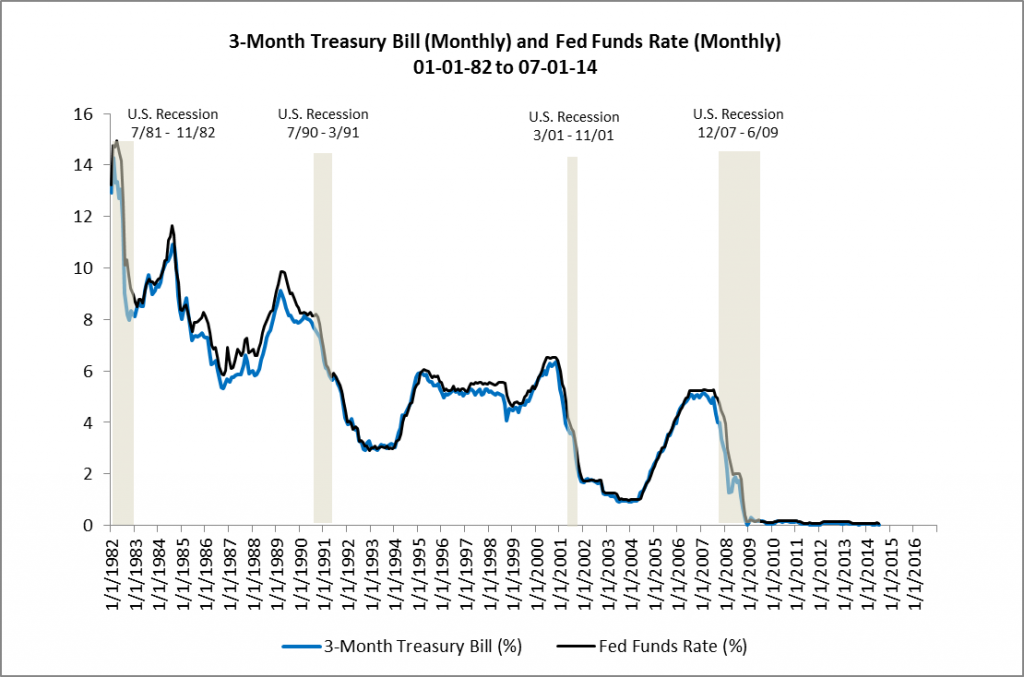

Next, we need to look for a reason for the volatility in the 3-Month Treasury Bill. Because the Federal Reserve is responsible for establishing short-term interest rates through its control of the Fed Funds Rate, comparing yields on the 3-Month Treasury Bill to the Fed Funds Rate is a good place to start. (See Figure 3.)

Figure 3: 3-Month Treasury Bill and Fed Funds Rate 01/01/82 to 07/01/14

Not surprisingly, yields on the 3-Month Treasury Bill move in virtual lock step with the Fed Funds Rate. This suggests that the Fed is responsible for the volatility in the 3-Month Treasury Bill through its control of the Fed Funds Rate and, by extension, is also largely responsible for changes in the spread between the 10-Year Treasury Note and the 3-Month Treasury Bill.

Now, if the spread between the 10-Year Treasury Note and 3-Month Treasury Bill accurately forecasts recessions, changes in the yields of the 3-Month Treasury Bill are largely responsible for changes in the 10-Year Treasury Note/3-Month Treasury Bill spread and the Fed’s control of the Fed Funds Rate is responsible for changes in the yield of the 3-Month Treasury Bill, it follows that changes in the Fed Funds Rate should also accurately forecast recessions.

Here’s where Austrian Business Cycle Theory (ABCT) comes in. Not only do changes in the Fed Funds Rate accurately forecast recessions, but the Fed’s manipulation of the Fed Funds Rate and yields on short-term Treasury securities actually causes the business cycle. That’s why the yield curves of Treasury securities forecast business cycles so well! For a thorough explanation of how the Federal Reserve causes the business cycle, see an earlier post on RealForecasts.com titled “Does The Federal Reserve Really Cause The Boom/Bust Cycle?”

What’s Next For The Fed Funds Rate And The 10-Year Treasury/3-Month Treasury Spread?

As of July 1, the spread between the 10-Year Treasury and 3-Month Treasury was 2.51%. (See Figure 1.) Because the Fed’s manipulation of the Fed Funds Rate causes the business cycle — and economic recessions occur once the spread between the 10-Year Treasury Note and 3-Month Treasury Bill approaches zero — it’s important to forecast the Fed’s actions and the 10-year Treasury/3-Month Treasury spread in the months ahead.

To begin, the Fed isn’t expected to raise the Fed Funds Rate until it ends its current round of quantitative easing, commonly referred to as QE3. In July, the Fed tapered its monthly bond buying to $25 billion and is on track to end QE3 in October of this year.

Next, the median estimate of Fed officials, released after the FOMC’s June meeting, forecasted an increase in the Fed Funds Rate to 1.13% at the end of 2015 and 2.5% by the end of 2016. According to the median of economists’ estimates in a Bloomberg survey, the Fed will first increase the Fed Funds Rate to 0.50% after its July, 2015 meeting. St. Louis Fed President James Bullard, who doesn’t vote on policy this year, has said that the Fed should increase the Fed Funds Rate at the end of March, depending on economic data.

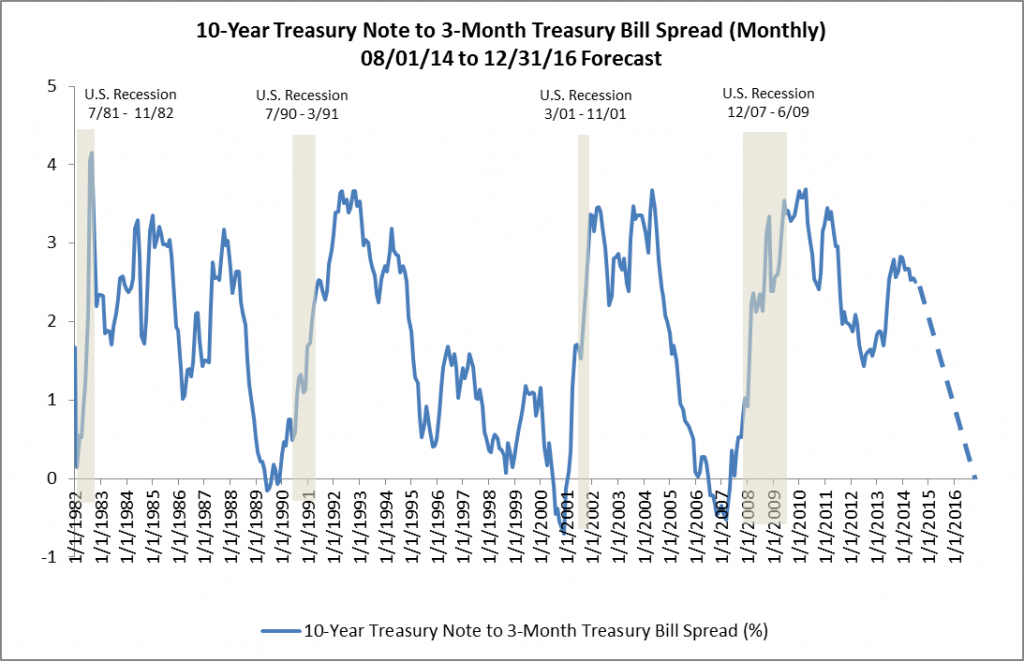

Once the Fed begins raising the Fed Funds Rate, look for the 10-Year Treasury/3-Month Treasury to begin narrowing. Because the spread is at 2.51% today, it’s likely that the Fed will have to raise the Fed Funds Rate by only 250 to 300 basis points before the spread approaches zero and the economy enters its next recession. If the Fed officials’ forecast mentioned above is accurate, that could occur by the end of 2016. (See Figure 4.)

Figure 4: 10-Year Treasury Note to 3-Month Treasury Spread 08/01/14 to 12/31/16 Forecast

So, for now, it appears that the Fed will begin to raise the Fed Funds Rate, and thereby begin to narrow the 10-Year Treasury/3-Month Treasury spread, in mid-2015 — give or take a quarter. It also appears that the Fed Funds Rate will reach 2.5%, the 10-Year Treasury/3-Month Treasury spread will approach zero and the economy will enter its next recession by the end of 2016. Continue to check back with RealForecasts.com for future updates about changes in the 10-Year Treasury/3-Month Treasury spread.