Editor’s Note: For its third post, RealForecasts.com is re-publishing a white paper titled “‘Deep Survival’ In Real Estate Investment Management – How To Survive (and Even Thrive) in 2009”, which was written in January of 2009. The advice applies to challenging situations today as much as it applied to the challenging market conditions we were going through almost five years ago.

“Deep Survival” In Real Estate Investment Management – How To Survive (and Even Thrive) in 2009

By Jeffrey J. Peshut

January, 2009

In his book Deep Survival: Who Lives, Who Dies and Why (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2003), Laurance Gonzales alternates compelling storytelling with first-rate scientific research to describe the art and science of survival. Although aimed primarily at wilderness travelers and extreme sports enthusiasts, Deep Survival is also a useful guide for anyone facing one of life’s great challenges.

Gonzales divides his book into two parts. In the first part, titled How Accidents Happen, Gonzales provides examples of people who got into trouble and how they got there. In the second part, titled Survival, he explores the character traits and behaviors of those that survived life-threatening situations.

The real estate investment management business is not a life or death environment. But the downturn in the economy is presenting challenges to our firm and our competitors that will undoubtedly change the landscape in our industry. Gonzales’ lessons provide a roadmap to not only survive, but also maximize opportunities during the downturn.

According to Gonzales, here is what survivors do (with suggestions about ways to apply these practices to the current business environment in italics):

1. Perceive and Believe: Even in the initial crisis, survivors’ perceptions and thought processes keep working. They notice the details. If they experience any denial, it is counterbalanced by strong confidence in the information provided by their five senses. They immediately begin to recognize, acknowledge and even accept the reality of their situation.

In the sport of orienteering, competitors have to navigate across unfamiliar terrain using a detailed map. If they ever start saying to themselves, “Well, that lake could have dried up,” or “That mountain could have moved,” they are doing what orienteers call “bending the map”. They are denying the reality before them and substituting the world they would rather see.

During 2009, we need to avoid “bending the map” and accept that market occupancy and market lease rates will decrease. We need to be prepared to meet the market when negotiating with both existing and prospective tenants.

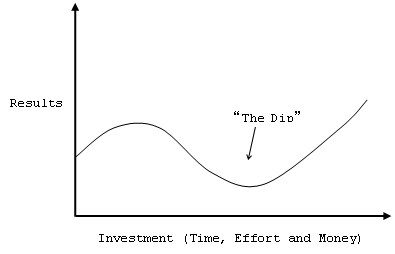

Similarly, we need to accept that required rates of return will continue to increase and property values will continue to decrease, especially for properties with higher risk profiles. If we do not have to sell, we need to prepare ourselves and our clients to hold their investments through the dip. If we have to sell, it will be best to do so sooner rather than later. Conversely, unless there is a very compelling opportunity, investors with capital should keep their powder dry and wait for the market to find a bottom before making new investments.

2. Stay Calm: In the initial crisis, survivors make use of fear and avoid being ruled by it. Their fear often feels like and is turned into anger, which motivates them and makes them sharper. They understand at a deep level the need to stay calm and are on constant guard against giving in to their emotions. They use humor to keep the situation in perspective. Those who can learn to think clearly and make good decisions under stress or in high emotional states are more likely to survive.

Market conditions will likely get worse before they get better. We need to remain calm and remind ourselves that conditions will eventually improve. They always have. They will again. In the meantime, we need to stay focused on maximizing property performance and strengthening our relationships.

3. Think/Analyze/Plan: Survivors quickly organize, set up routines and institute discipline. They push away thoughts that their situation is hopeless. A rational voice emerges and is often actually heard, which then takes control of the situation. Survivors describe this experience as a feeling of “splitting” into two people and then “obeying” the rational one. It begins with the paradox of seeing the stark reality but acting with the expectation of success.

We need to be realistic about the difficulty of the market conditions we expect to encounter during 2009 and 2010, but optimistic about our ability to succeed in the face of these conditions. That is very different from simply being optimistic about expected conditions.

4. Take Correct, Decisive Action: Survivors are able to transform thought into action. They are willing to take risks to save themselves and others. They are able to break down very large jobs into small manageable tasks. They set attainable goals and develop short-term plans to reach them. They are meticulous about doing those tasks well. They deal with what is within their power from moment to moment, hour to hour and day to day. They leave the rest behind.

Although we cannot do anything about the increasing rates of return and the decreasing lease rates we will encounter in the coming year, we can take steps to maintain and build our relationships with our clients. We can also take steps to maintain and build the occupancy of our properties and portfolios. And rather than waiting for one large tenant to lease a large block of vacant space, we need to be prepared to break it up into smaller increments to attract smaller tenants – which are typically more prevalent in the market.

5. Celebrate Successes: Survivors take great joy from even their smallest successes. That is an important step in creating an on-going feeling of motivation and preventing a descent into hopelessness. It also provides relief from the suffocating stress of a true survival situation.

Most inexperienced mountain climbers make the mistake of celebrating on the summit, even though the hardest part of the trip is still before them — getting back down. Experienced climbers know that most accidents happen on the way down, when they are tired and more likely to drop their guard. Companies and even individual careers are subject to the same rules: We are most vulnerable at the top of the market and at those times when we feel most secure and confident. Like inexperienced mountain climbers, most companies do not plan for the trip back down.

During 2009, we need to take time to celebrate our successes, no matter how small.

6. Count Their Blessings: This is how survivors become rescuers instead of victims. There is always someone else they are helping more than themselves, even if that someone else is not present.

As Steve Furnary said in his year-end message, we have much for which to be thankful. We have a great company, made up of great people and excellent relationships with over 250 clients. We have also reported great returns over the past several years, which will continue to show up in our reported returns going forward.

7. Believe That They Will Succeed: All of the practices just described lead to this point. Survivors consolidate their personalities and fix their determination. Survivors admonish themselves to make no more mistakes, to be very careful and to do their very best. They become convinced that they will prevail if they do these things.

Down markets provide an opportunity for great companies to distinguish themselves from their competitors and actually increase their market share. To paraphrase Warren Buffet, no one can tell who is swimming naked until the tide goes out. We are already capitalizing on this opportunity as we take over properties and portfolios from competitors such as Morgan Stanley and RREEF. Somebody is going to come out on top during this next phase of the market cycle. It might as well be us.

8. Surrender: This sort of thinking has been called “resignation without giving up” or “survival by surrender.” A climber recognizes that he will probably die, doesn’t let it bother him and goes ahead and crawls off the mountain anyway. Survivors also manage pain well. One woman, who walked out of the Sierra Nevada Mountains after surviving a plane crash, wrote that she “stored away the information” that her arm was broken.

It will be painful as our values continue to decline during 2009. We will have to make some difficult decisions – accepting lower than pro forma rents, leasing to higher risk tenants, even selling at a loss. We need to “put away” that pain and focus on the things we can control, including our relationships with our clients, with our tenants and among ourselves. The short-term pain will pay off when we are able to enjoy the long-term rewards.

9. Do Whatever is Necessary: Survivors have “meta-knowledge” – loosely defined as “knowledge about knowledge.” They know what they know and they know what they do not know. In particular, they know their abilities and do not over or under estimate them. That said, they still believe that anything is possible and act accordingly. Play leads to invention, which leads to trying something that might have seemed impossible.

Survivors do not expect or even hope to be rescued. They are coldly rational about using the world, obtaining what they need and doing what they have to do.

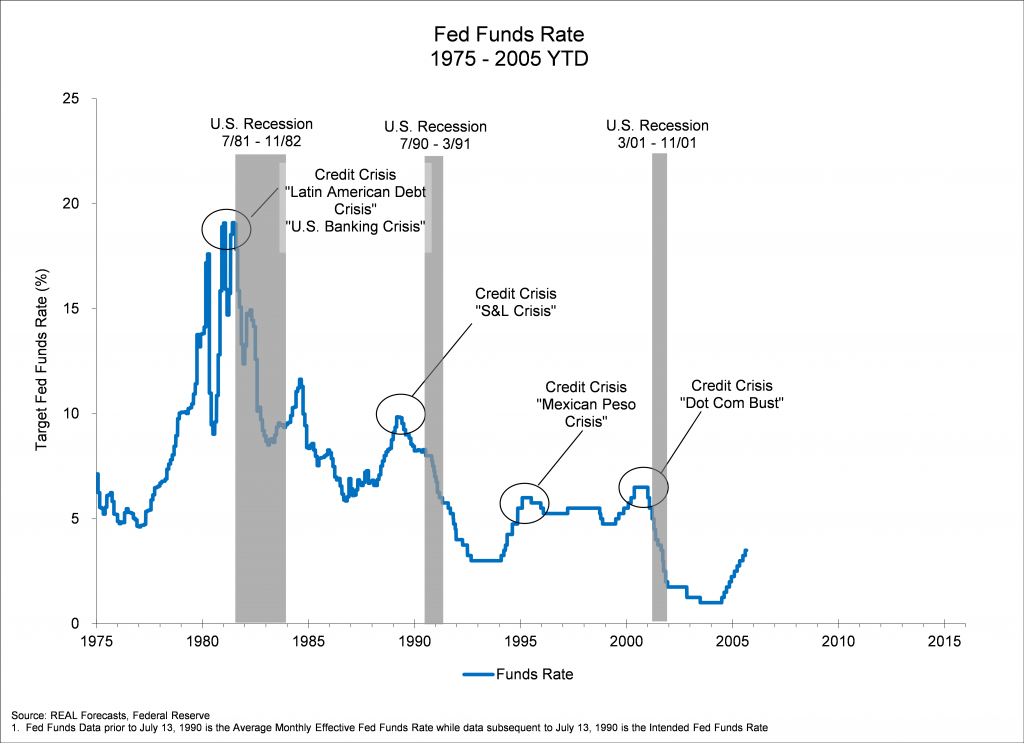

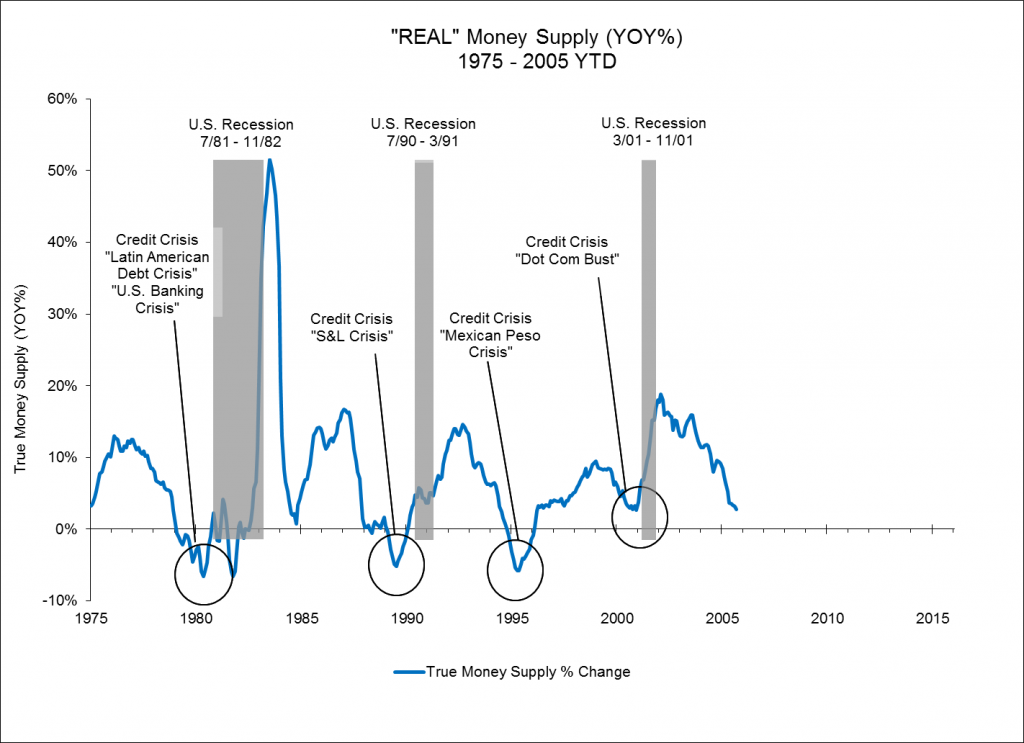

It will not do us any good to wait around for the Fed, the White House or Congress to rescue us from our current situation. We need to take responsibility for our own attitudes and our own actions and do what we have to do for our clients, our company and ourselves.

10.Never Give Up: Survivors are not easily frustrated. They are not discouraged by setbacks. They accept that their environment is constantly changing. There is always one more thing that they can do. They pick themselves up and start the entire process over again, breaking it down into manageable bits.

Survivors always have a clear reason for going on. They keep their spirits up by developing an alternate world made up of rich memories to which they can escape. They then mine those memories for whatever will keep them occupied. They come to embrace the world in which they find themselves and see opportunity in adversity.

In the aftermath, survivors learn from and are grateful for the experiences they have had.

Winston Churchill may have said it best, “Never, never, never give up.”

In Deep Survival, the wilderness is a metaphor for all of life’s challenges. And the survivors of these challenges have universal lessons to teach us all – even those of us traveling through the wilderness of real estate investment management during 2009.