By Jeffrey J. Peshut

September 3, 2019

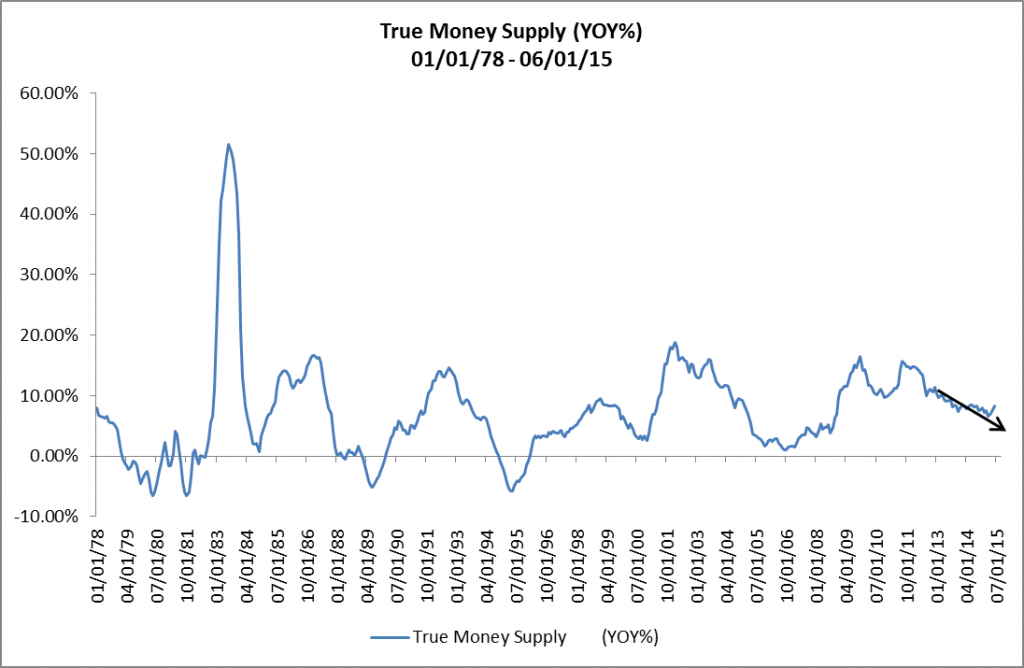

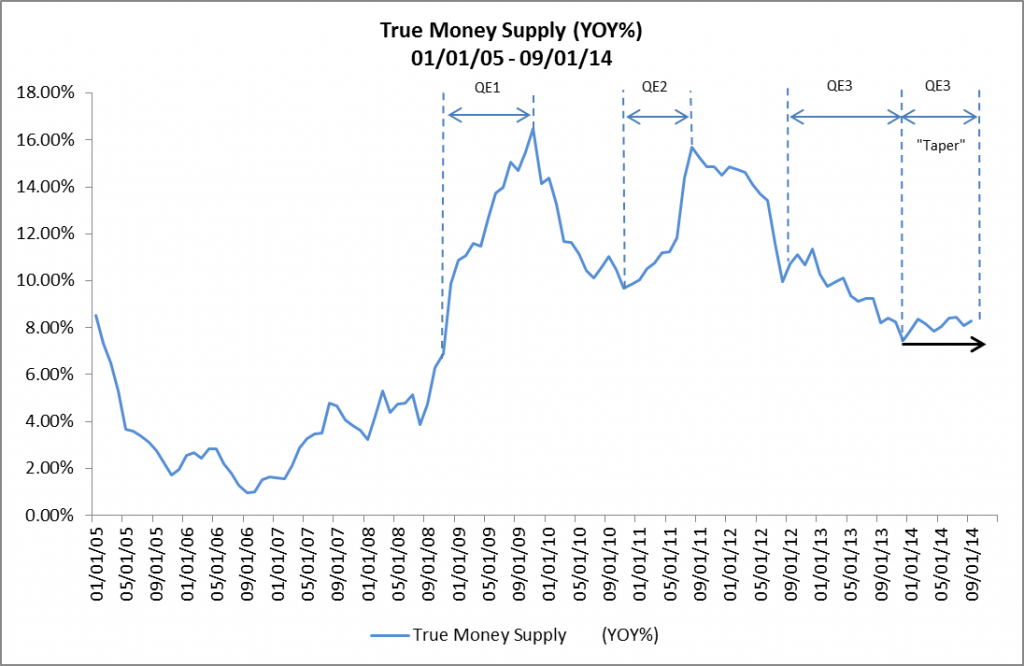

Since March of this year, the year-over-year growth rate of the True Money Supply (“TMS”) has hovered around 2%, the lowest growth rate since March of 2007. Further, at its July 30-31, 2019 meeting, the Federal Open Market Committee agreed to lower the target range for the Federal Funds Rate (“FFR”) by 25 basis points from 2.25% to 2.50% to 2.0% to 2.25%. Because the TMS moves inversely with the FFR, this raises the question of whether the FOMC’s recent action forecasts the acceleration of the growth of TMS, thereby indicating that the growth rate of TMS reached its nadir for this cycle during 2019’s March through August time-frame. This post will attempt to answer this question and explore the implications of the answer to real estate investors.

True Money Supply Update

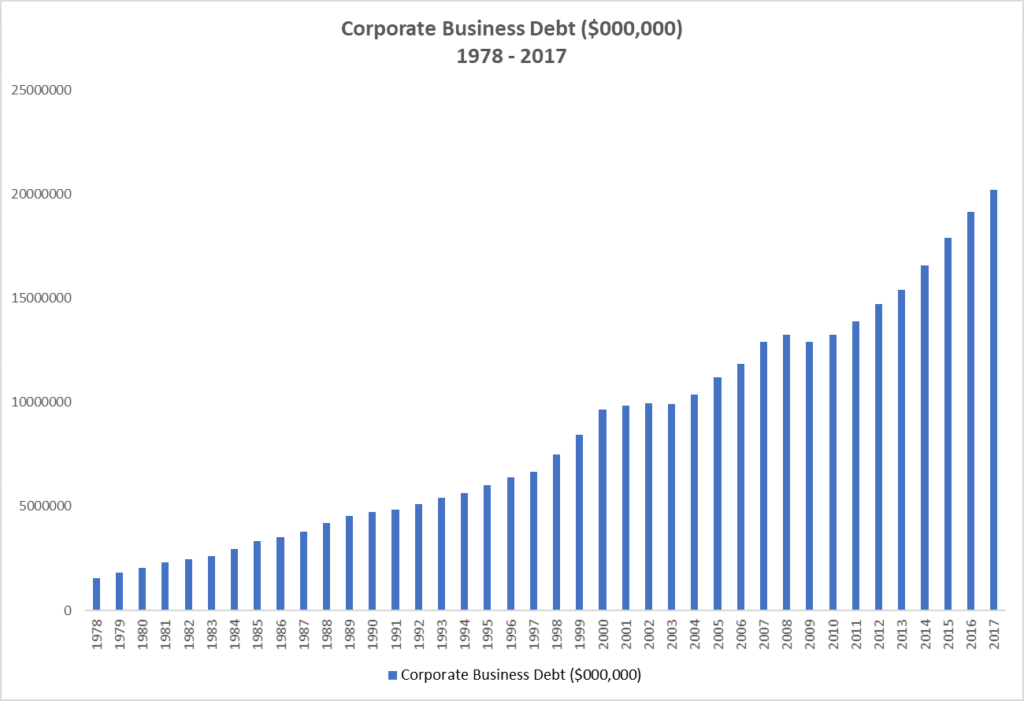

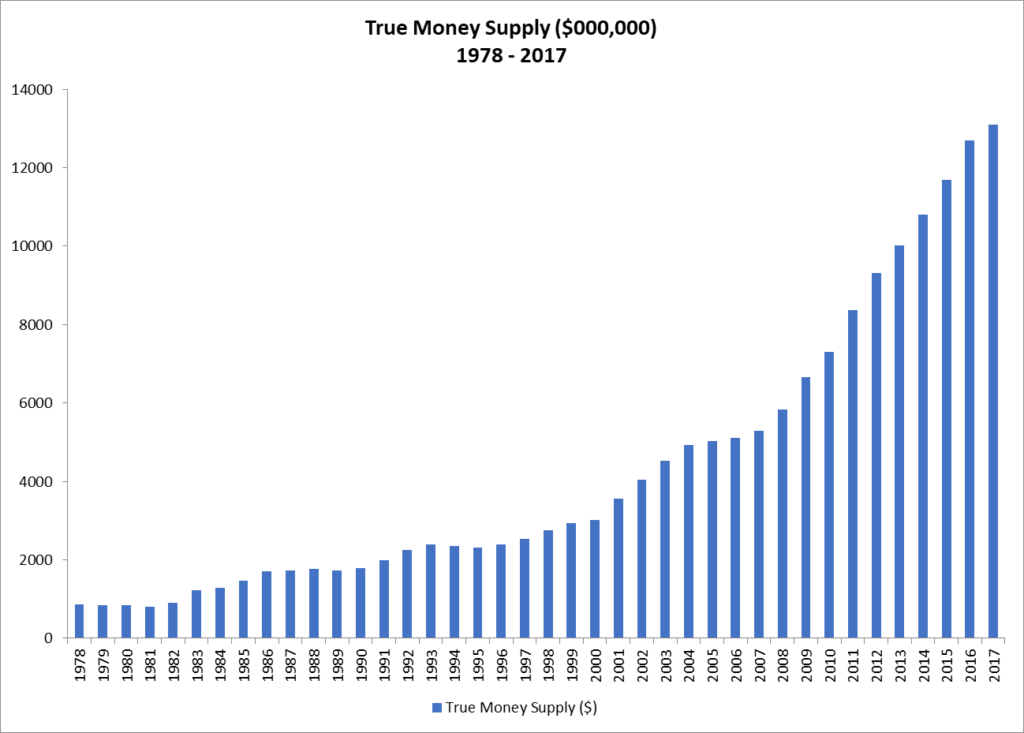

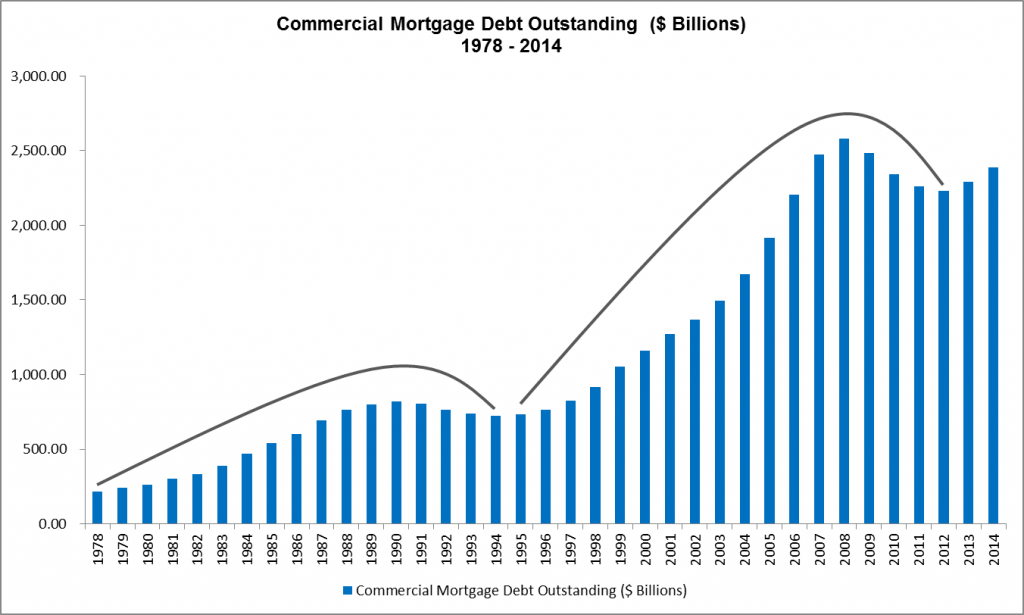

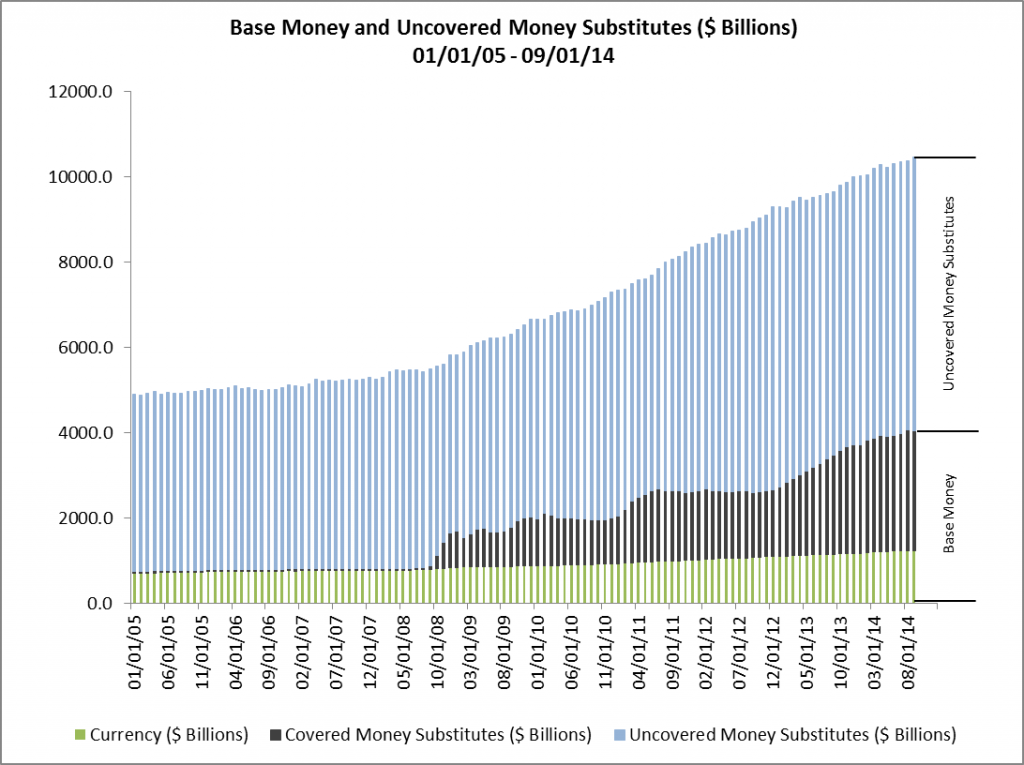

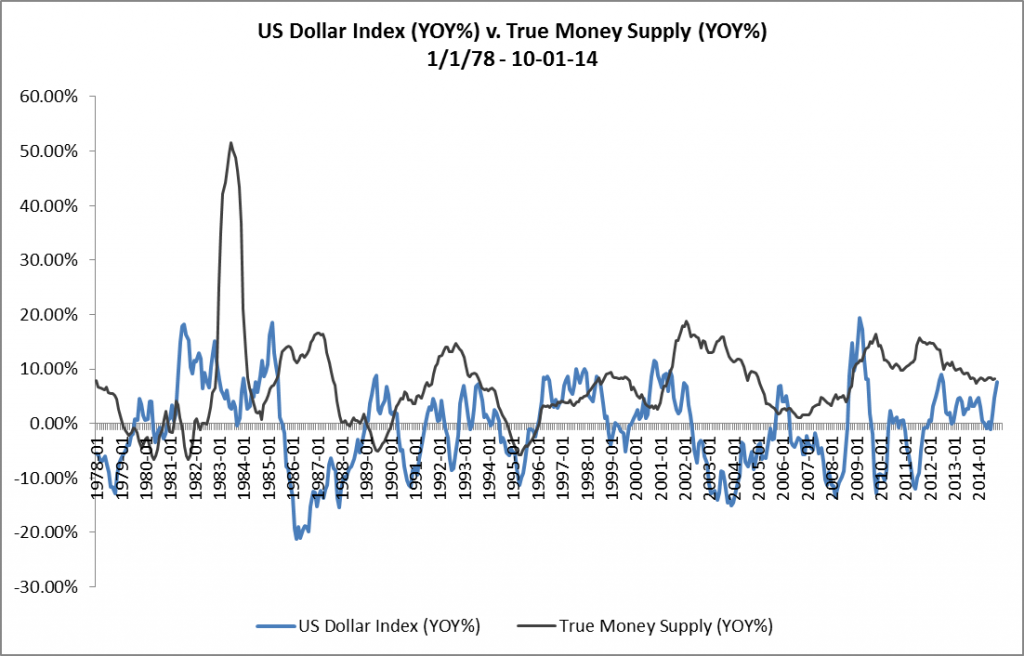

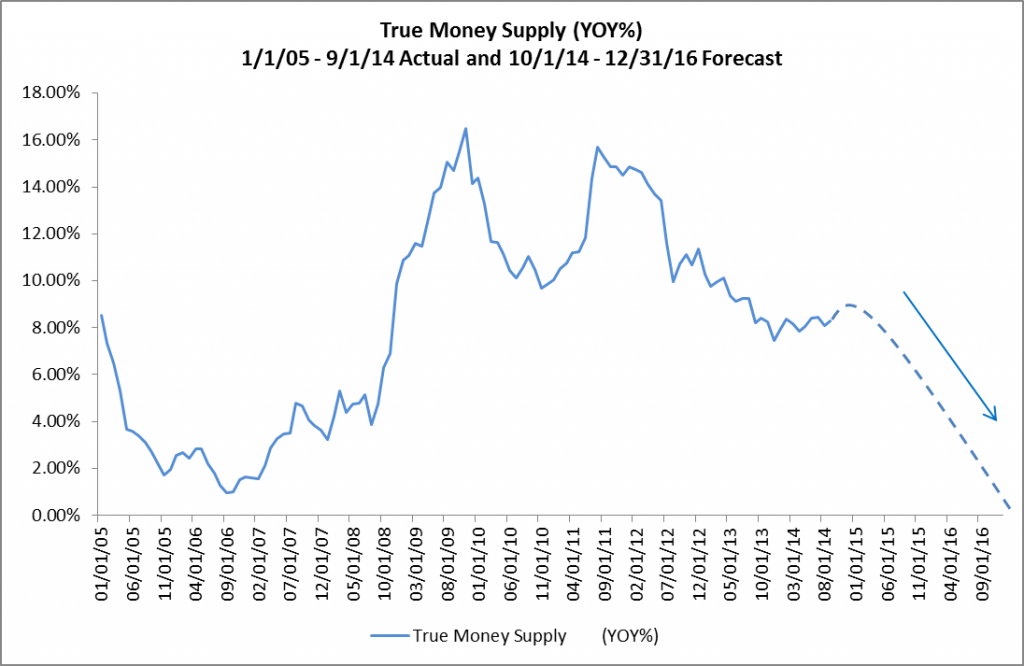

The total amount of the True Money Supply from January 1, 1978 through August 1, 2019 is shown in Figure 1. In August of 2019, TMS totaled $13.7 trillion, an increase of $8.7 trillion from the cyclical low of $5.0 trillion in August of 2006. This represents an exponential increase of 174% over the 13 year period.

Figure 1: True Money Supply ($000,000) 01-01-78 – 08-01-19

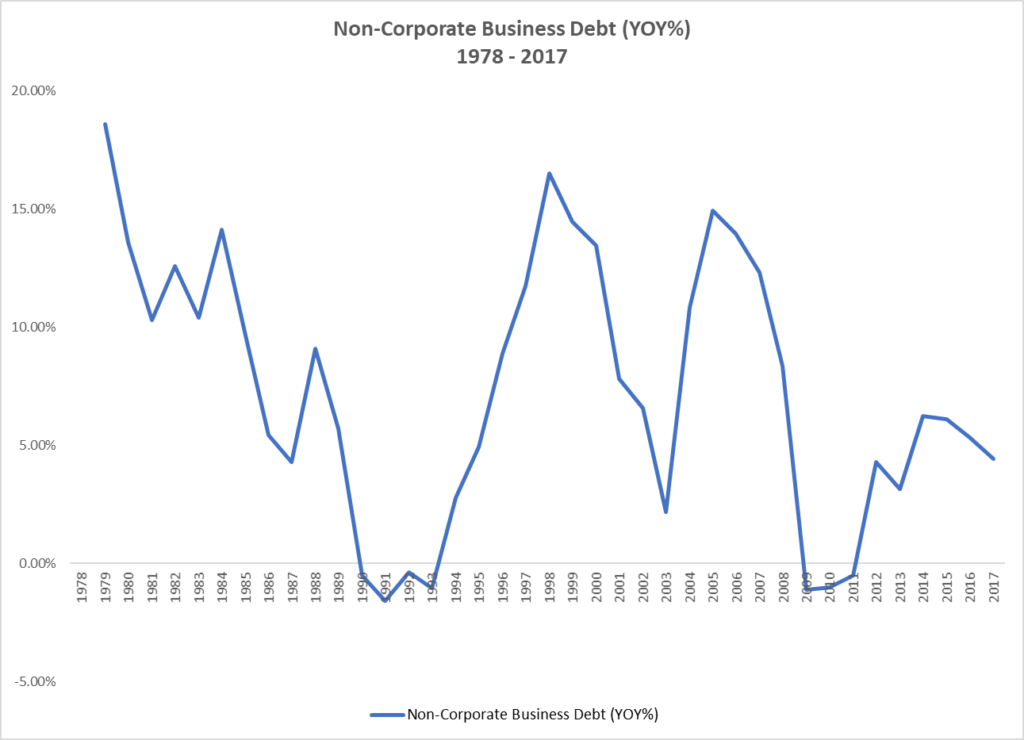

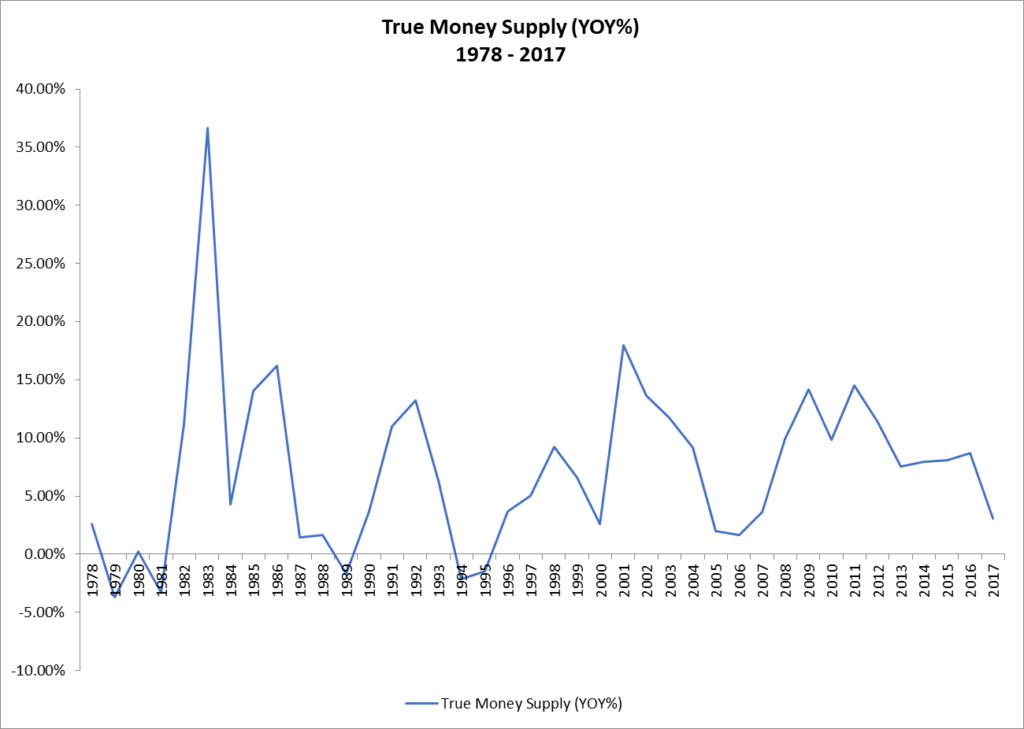

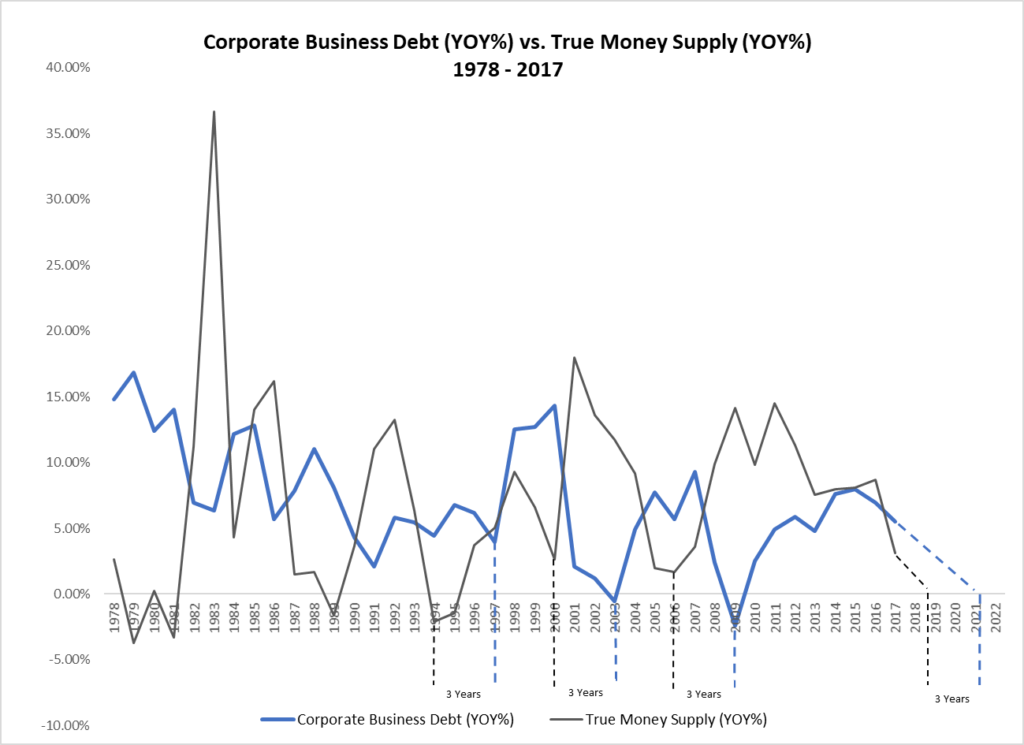

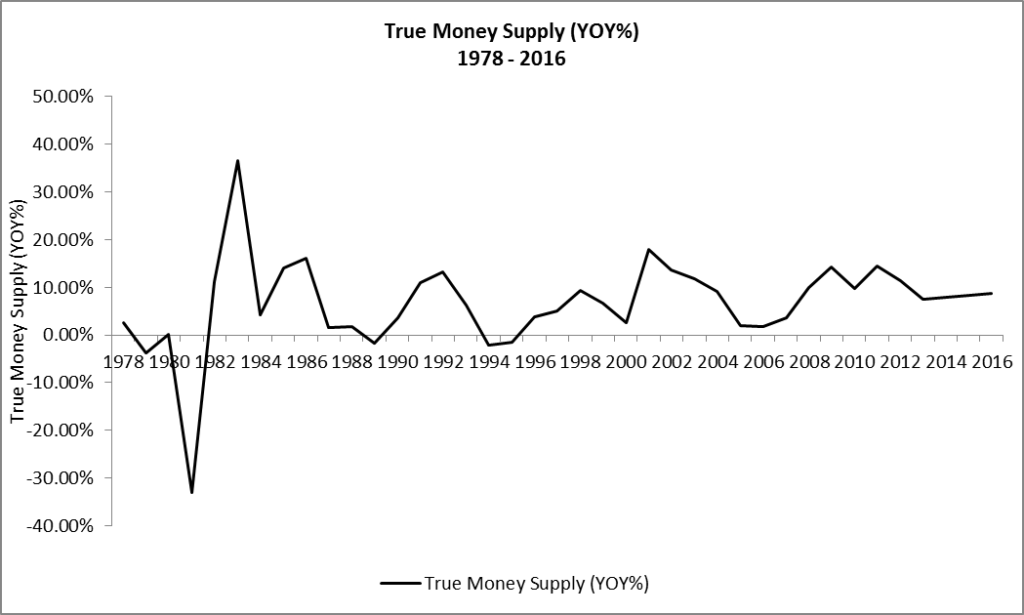

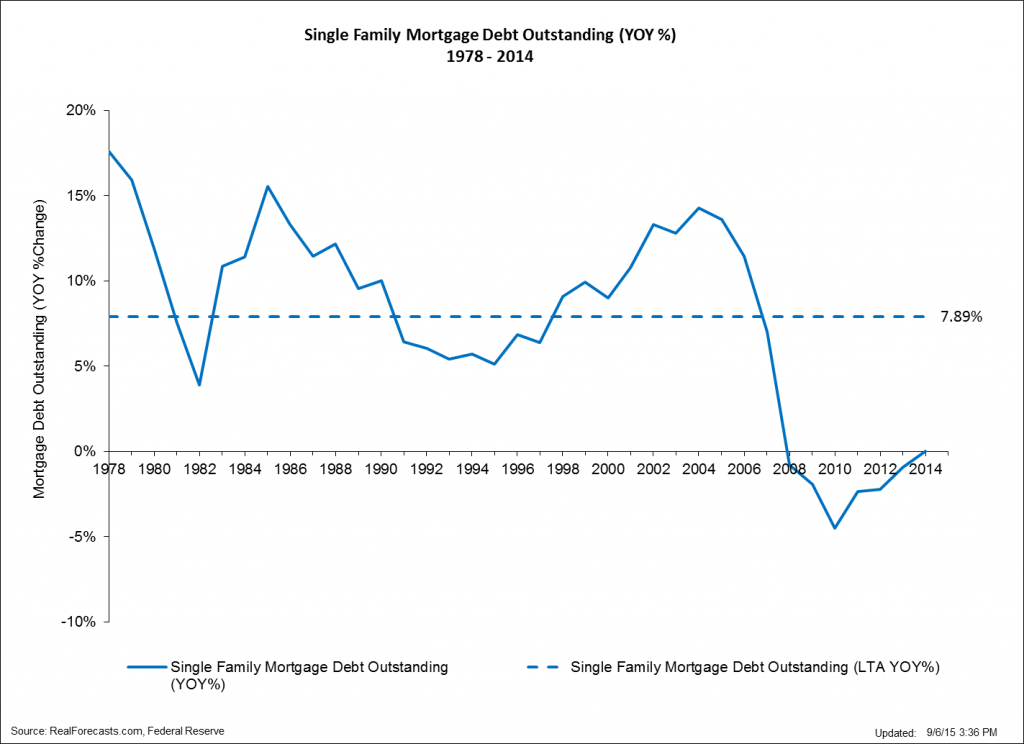

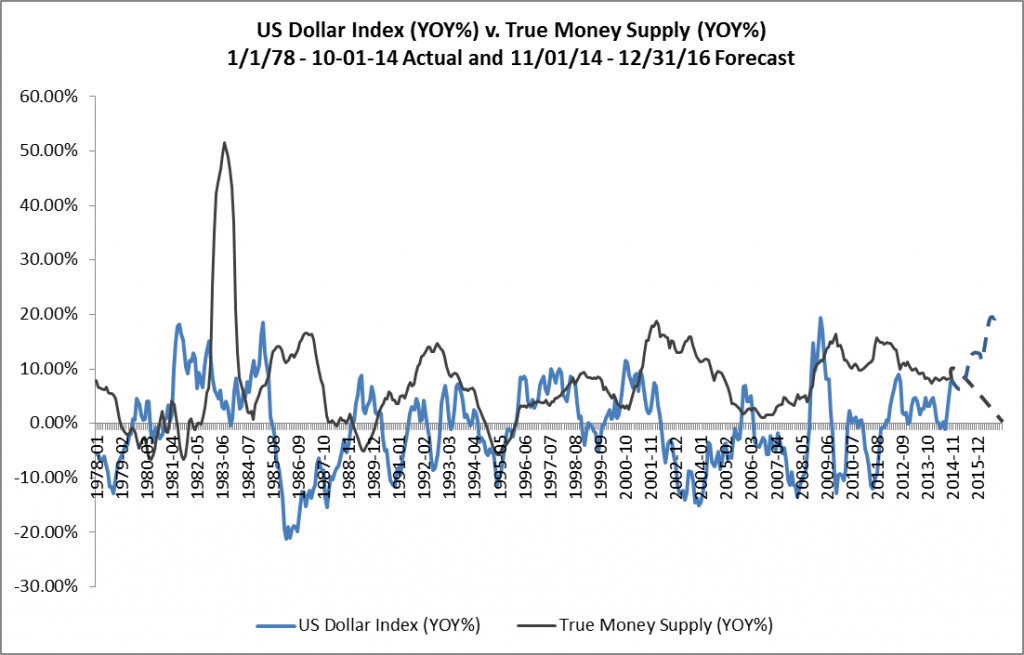

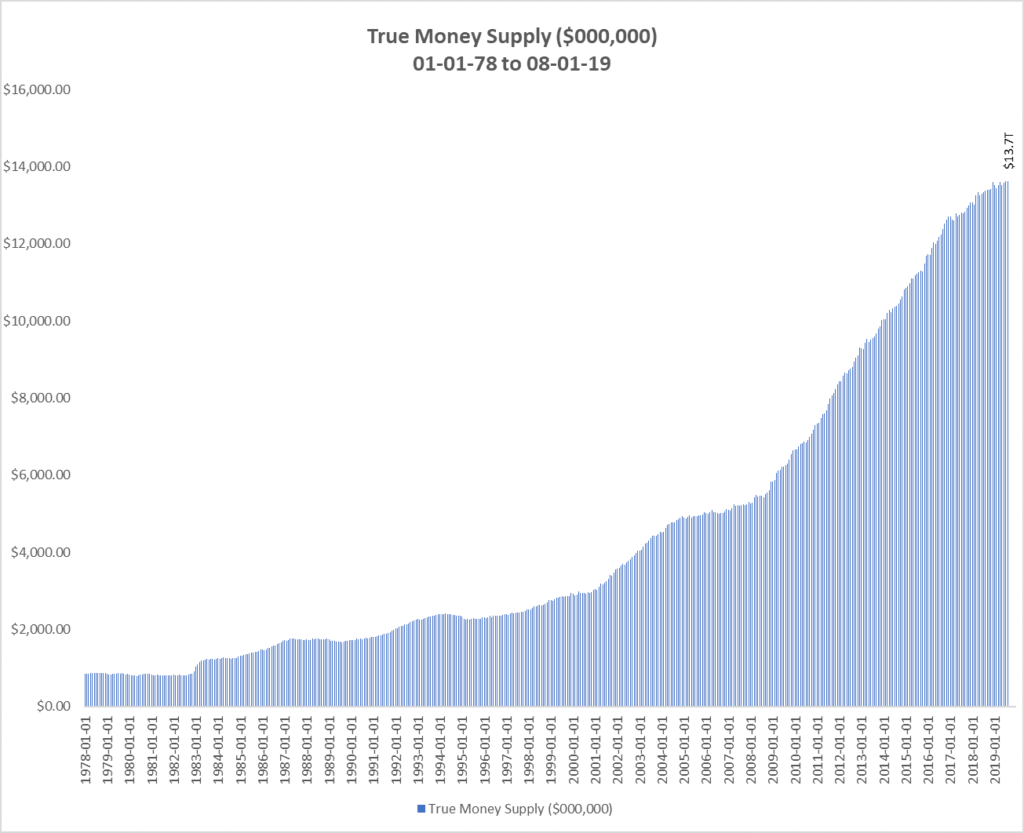

The year-over-over year percentage growth of TMS from January 1, 1978 through August 1, 2019 is shown in Figure 2. The average year-over-year growth rate of TMS over the past 40 years has been 7.24%.

Figure 2: True Money Supply (YOY%) 01-01-78 – 08-01-19

Note the cyclical peaks in the year-over-year growth of TMS of 51.53% in 1983, 14.23% in 1992, 18.02% in 2001 and what will likely be the peak for the current cycle of 15.26% in 2011. Also note the cyclical troughs in the TMS growth rate of -4.87% in 1989, -5.79% in 1995, 2.61% in 2000 and .98% in 2006. Based upon the precipitous drop in the TMS growth rate between October of 2016 and February of 2019 and the flat growth rate of approximately 2% since March, it appears that the deceleration in the growth of TMS has leveled off and the TMS growth rate may have reached its cyclical low.

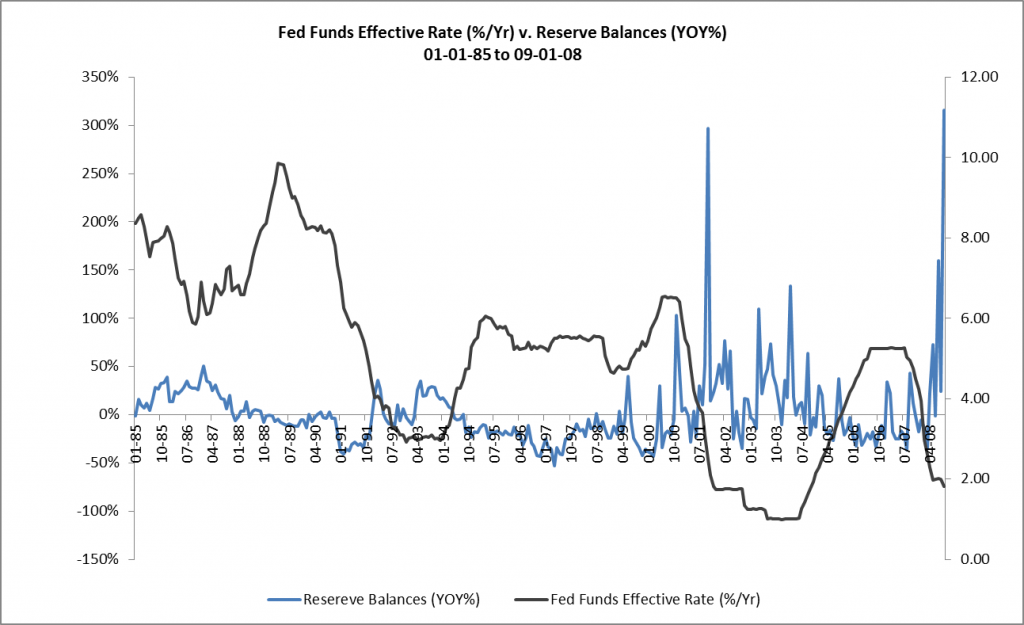

Relationship Between Federal Funds Rate and True Money Supply

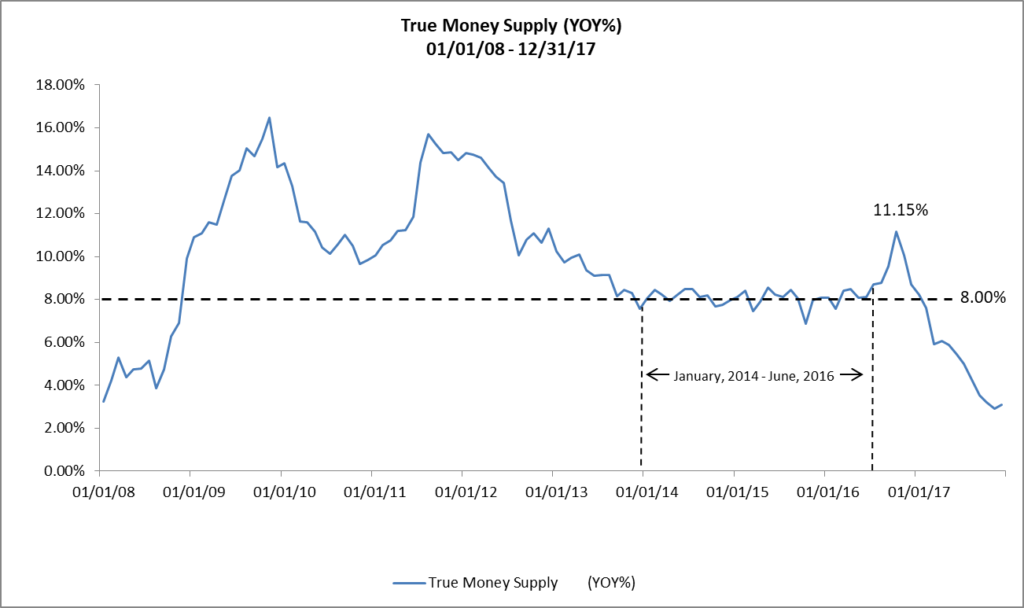

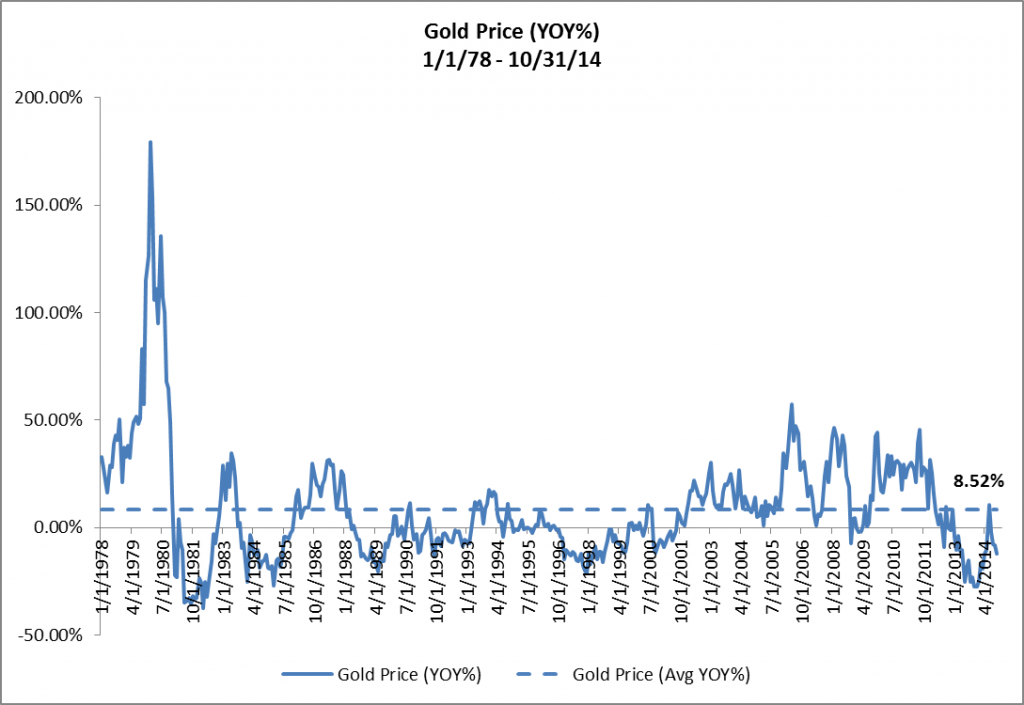

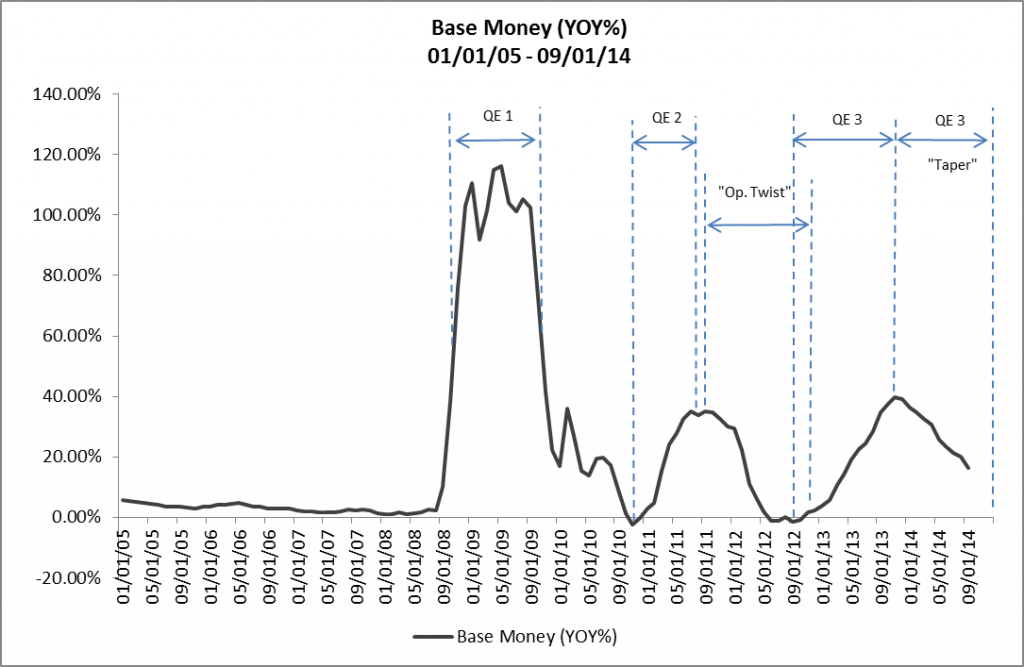

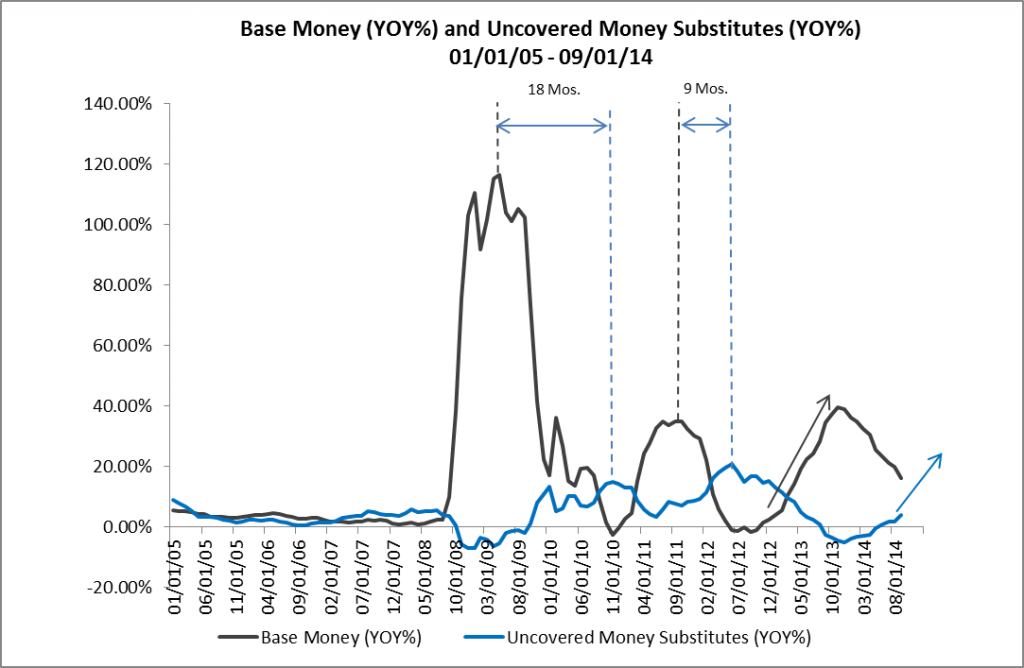

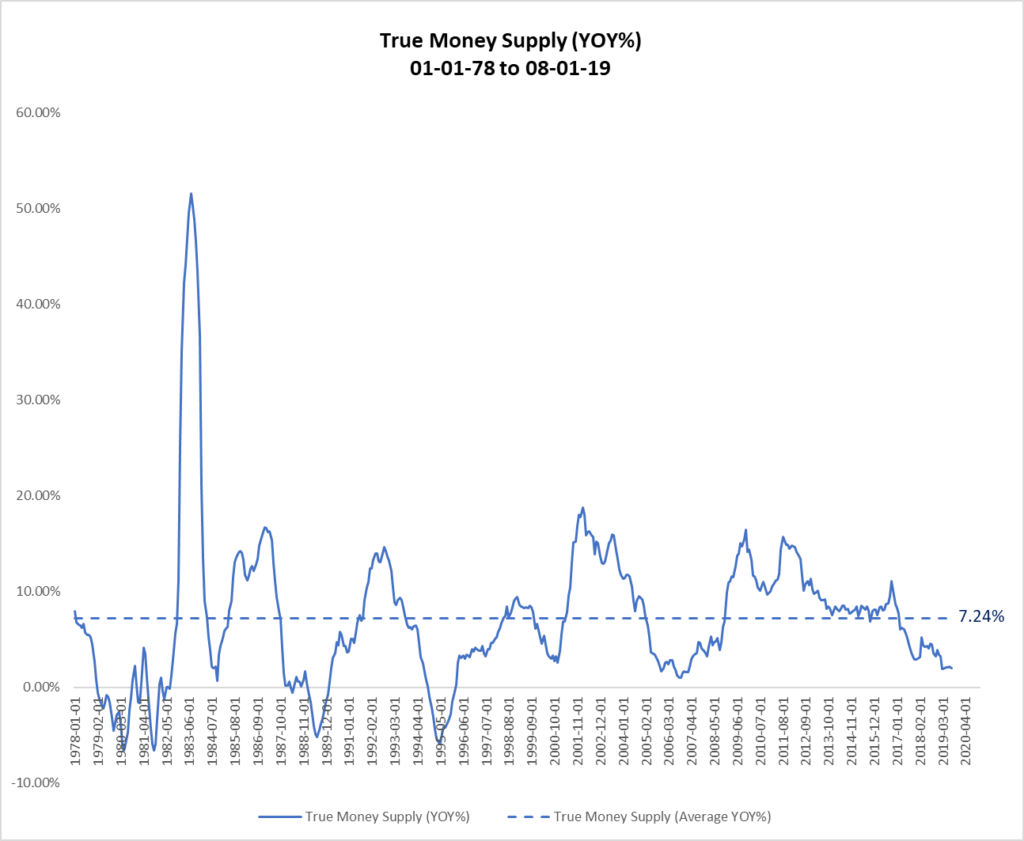

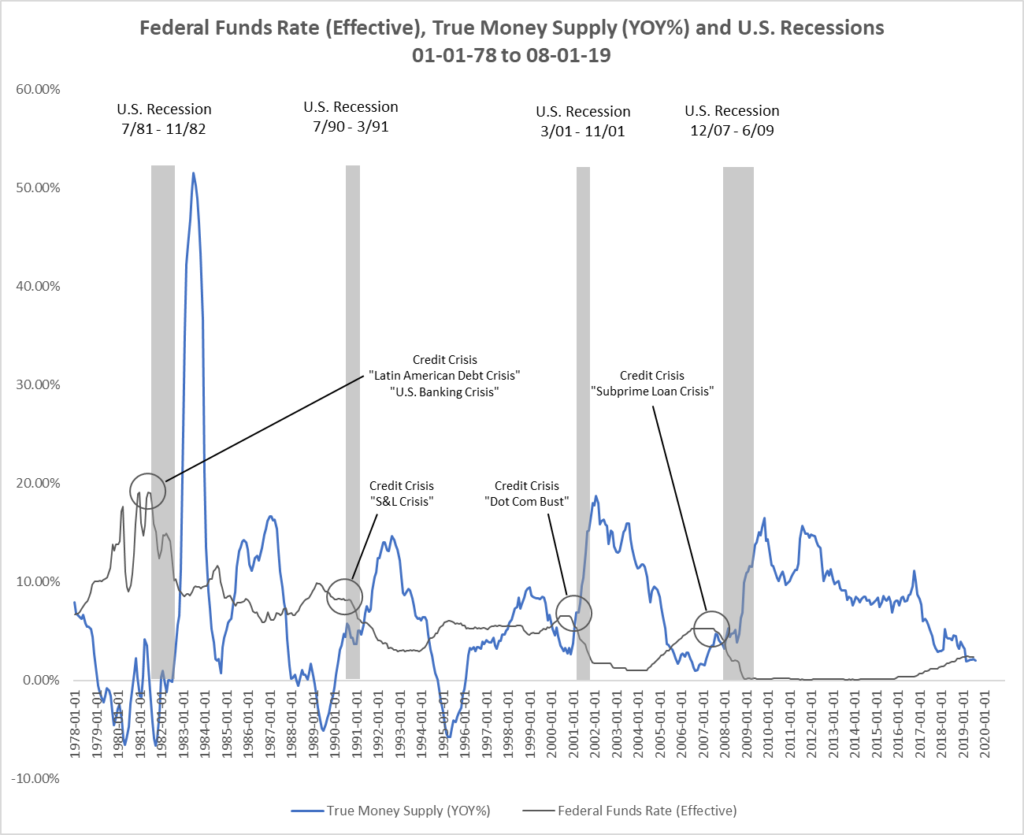

The FOMC’s recent decision to lower the target range for the Federal Funds Rate by 25 basis points is another sign that the TMS growth rate may have reached its cyclical low. Figure 3 clearly shows the inverse relationship between changes in the FFR and changes in the growth rate of TMS.

Figure 3: True Money Supply (YOY%) vs. Federal Funds Rate (Effective) 01-01-78 – 08-01-19

Note that the peaks in the Federal Funds Rate correspond to troughs in the growth rate of TMS and vice versa. Thus, when the FOMC adopts an accommodative monetary policy stance and begins lowering the FFR, growth in TMS accelerates. Conversely, when the FOMC adopts a tight policy stance and begins raising the FFR, growth in TMS decelerates.

In the current cycle, the FOMC began raising the FFR at the beginning of 2016. On cue, in late-2016, the growth in TMS began to decelerate. The FOMC continued to raise the FFR — and the growth in TMS continued to decelerate — until just recently when the TMS growth rate flattened.

Implications To Real Estate Investors

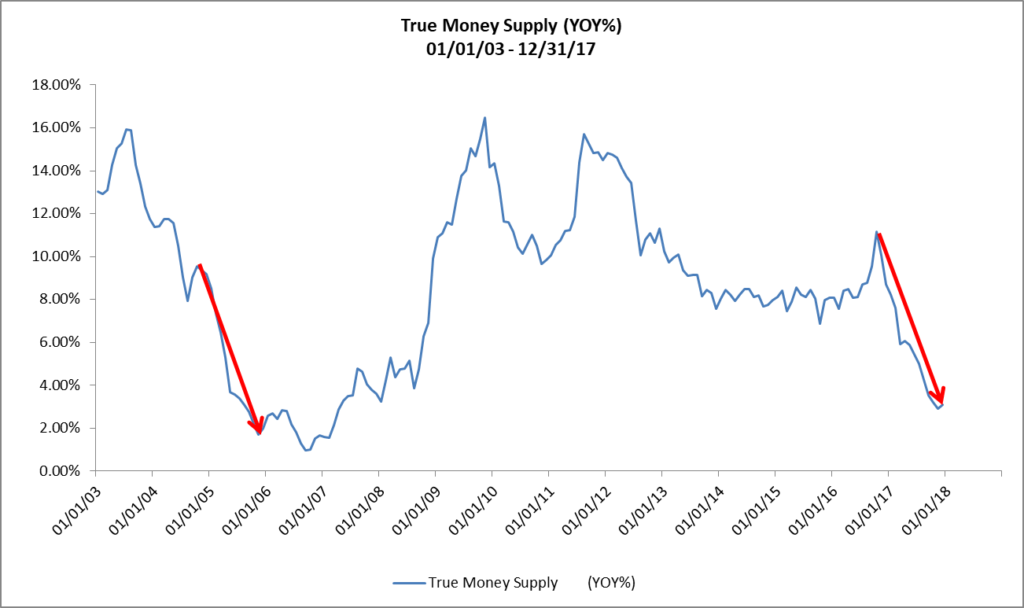

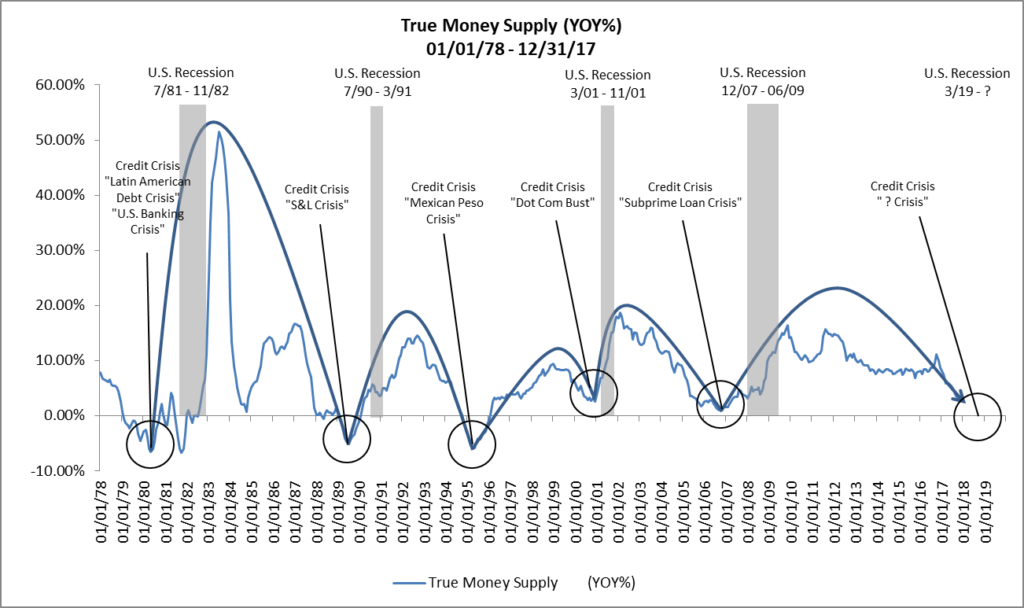

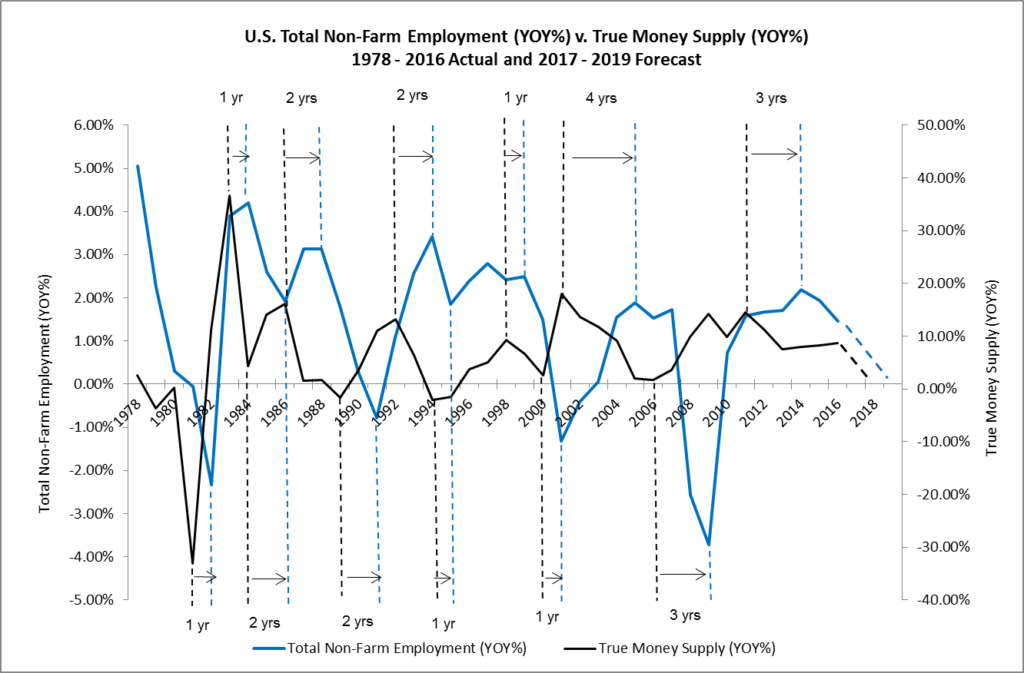

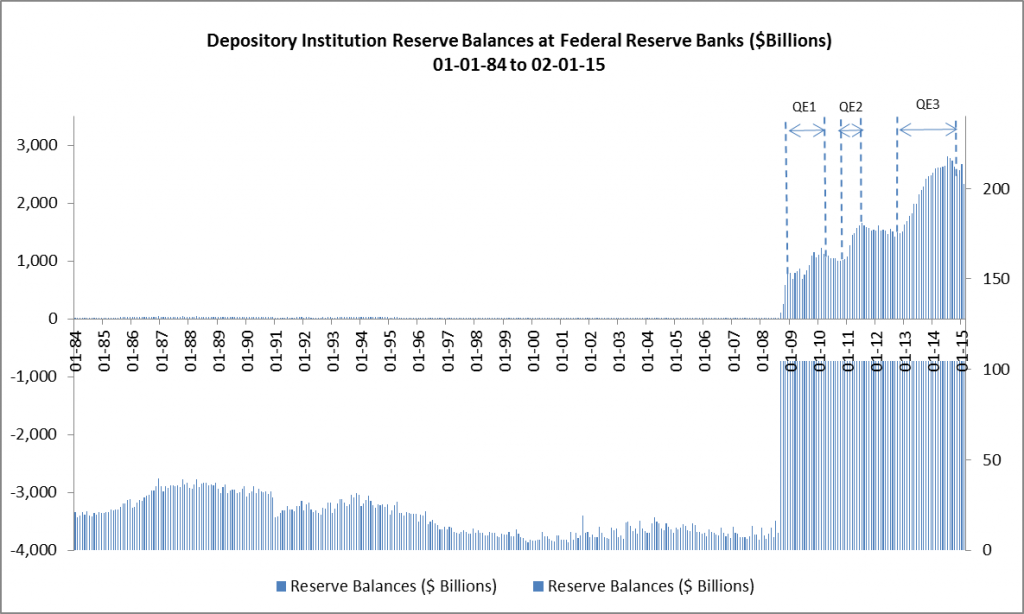

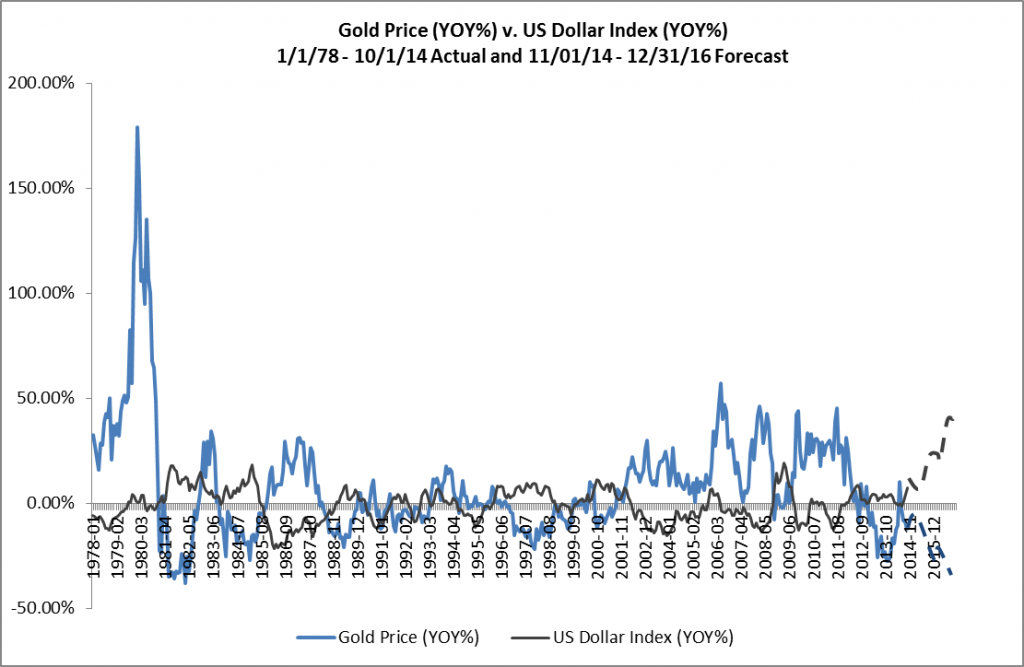

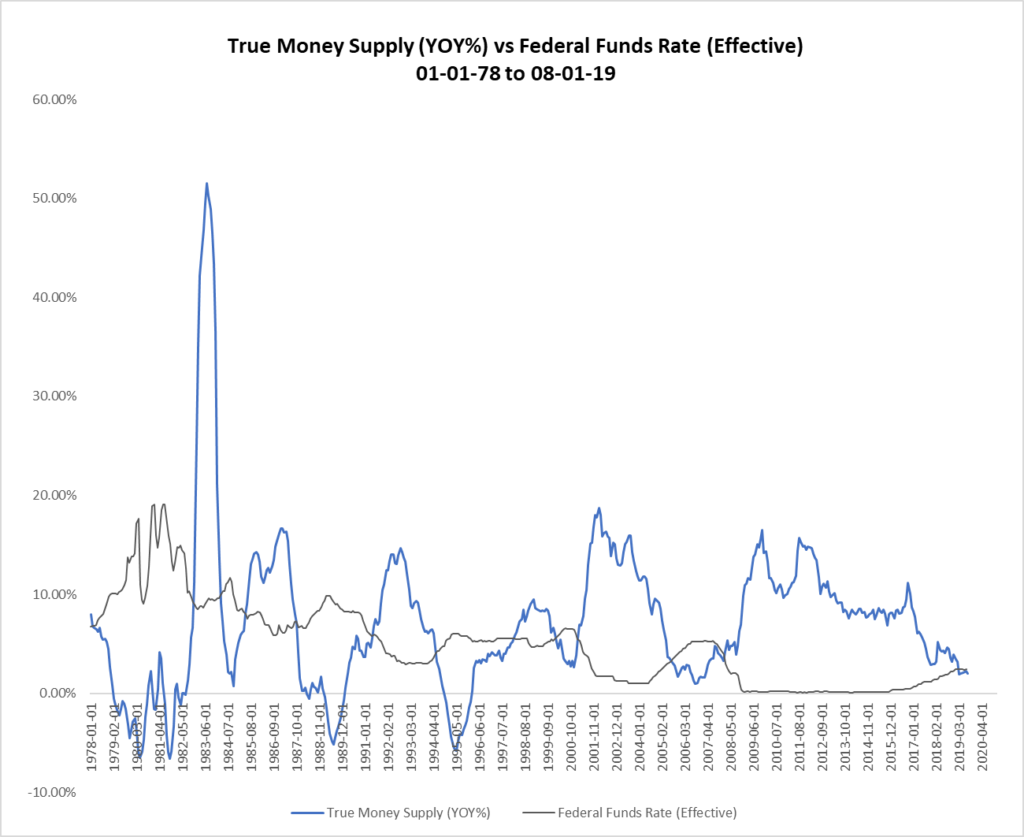

So, why is all of this so important to real estate investors? Because a deceleration in the year-over-year growth rate of TMS to a point at which the FOMC begins to lower the FFR has preceded the last four economic recessions in the U.S. For example, a deceleration in the year-over-year growth rate of TMS to 2.6% in early-2000 and the FOMC’s decision to lower the FFR in response preceded the Dot Com Bust and the economic recession that began in March of 2001. Similarly, the deceleration in the year-over-year growth rate of TMS to just under 1% in late-2006 and the FOMC’s decision to lower the FFR in response preceded the Subprime Loan Crisis and the Great Recession that began in December of 2007. (See Figure 4.)

Figure 4: Federal Funds Rate (Effective), True Money Supply (YOY%) and U.S. Recessions 01-01-78 – 08-01-19

Of course, regular readers of RealForecasts.com know that Austrian Business Cycle Theory provides the only accurate explanation for this relationship among changes in the FFR, changes in TMS and economic recessions. (See, Does the Federal Reserve Really Create The Boom/Bust Cycle?)

Federal Funds Rate and True Money Supply Forecast

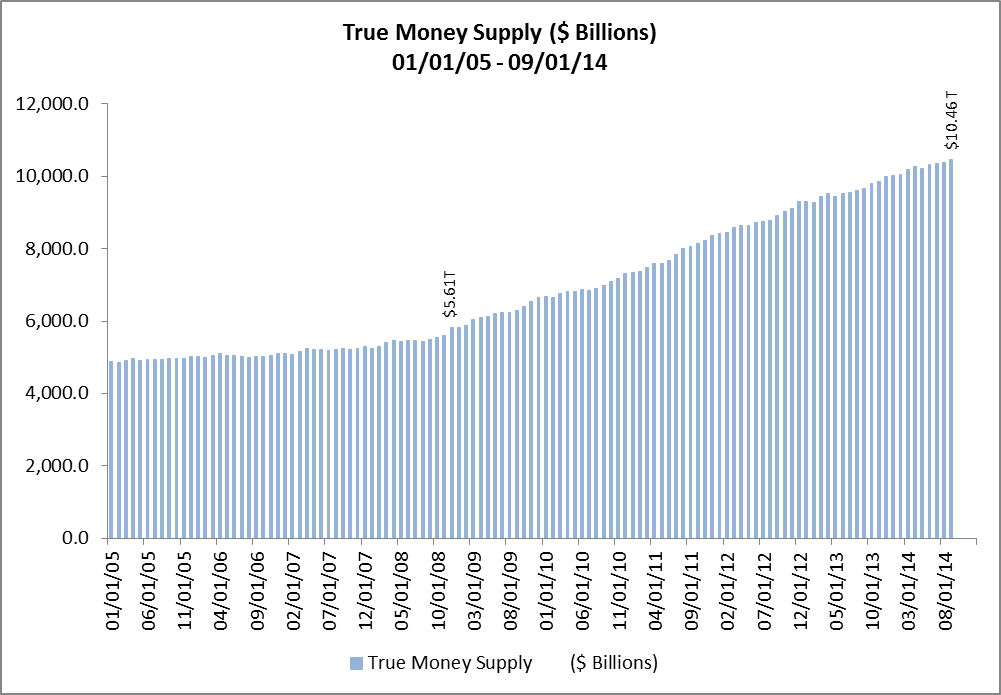

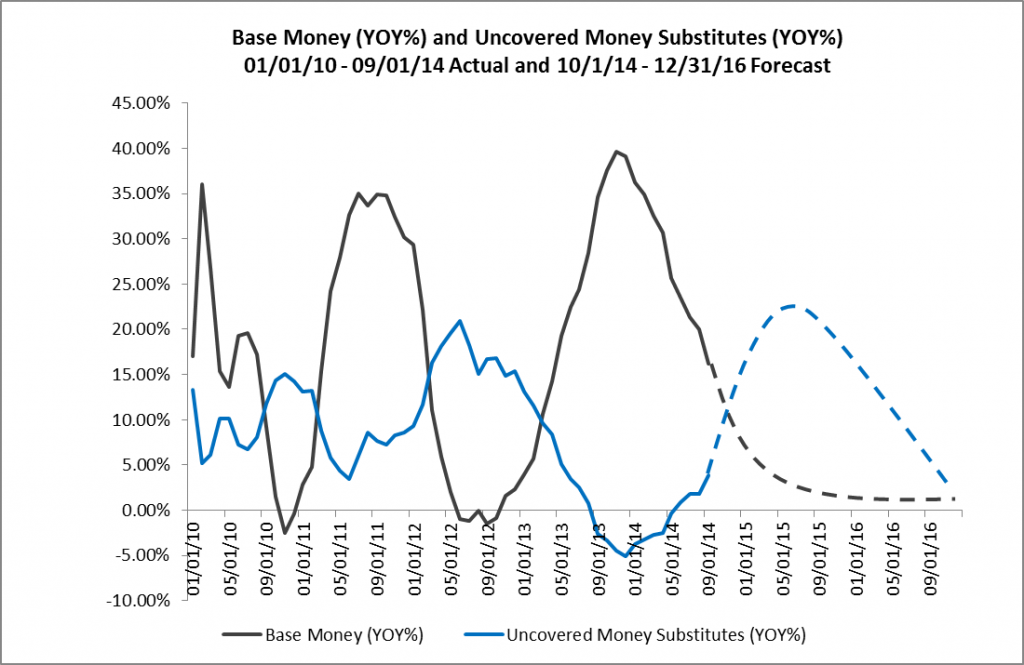

Once the FOMC shifts its monetary policy stance from accommodative to tight or tight to accommodative, it will continue with that stance until it believes that its policy objectives have been achieved. It may vary the speed of implementation, but the direction remains consistent. The FOMC doesn’t jump back and forth between policies.

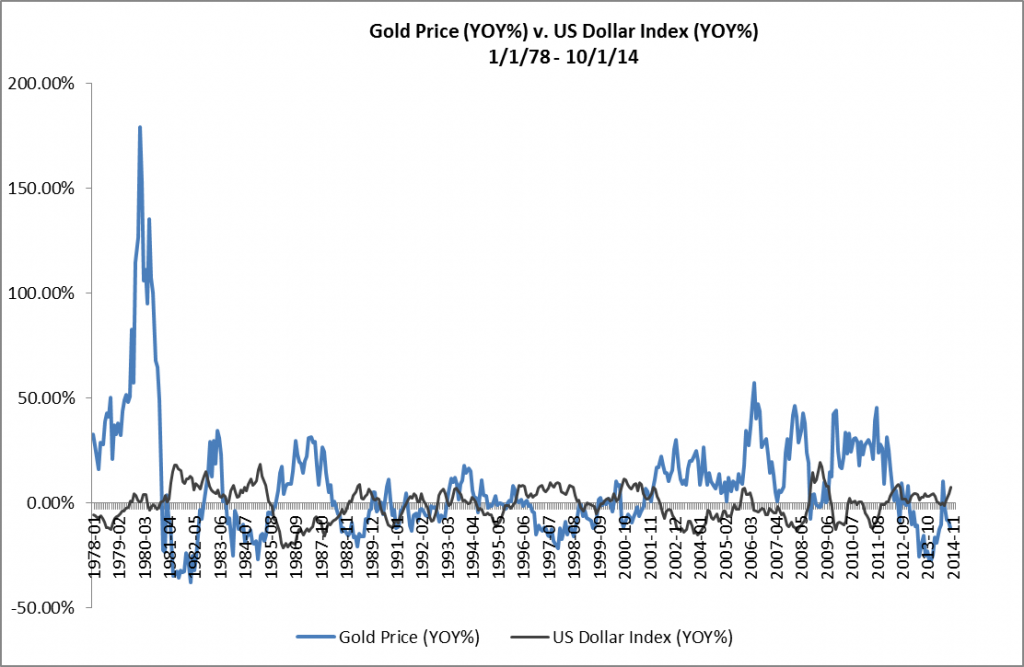

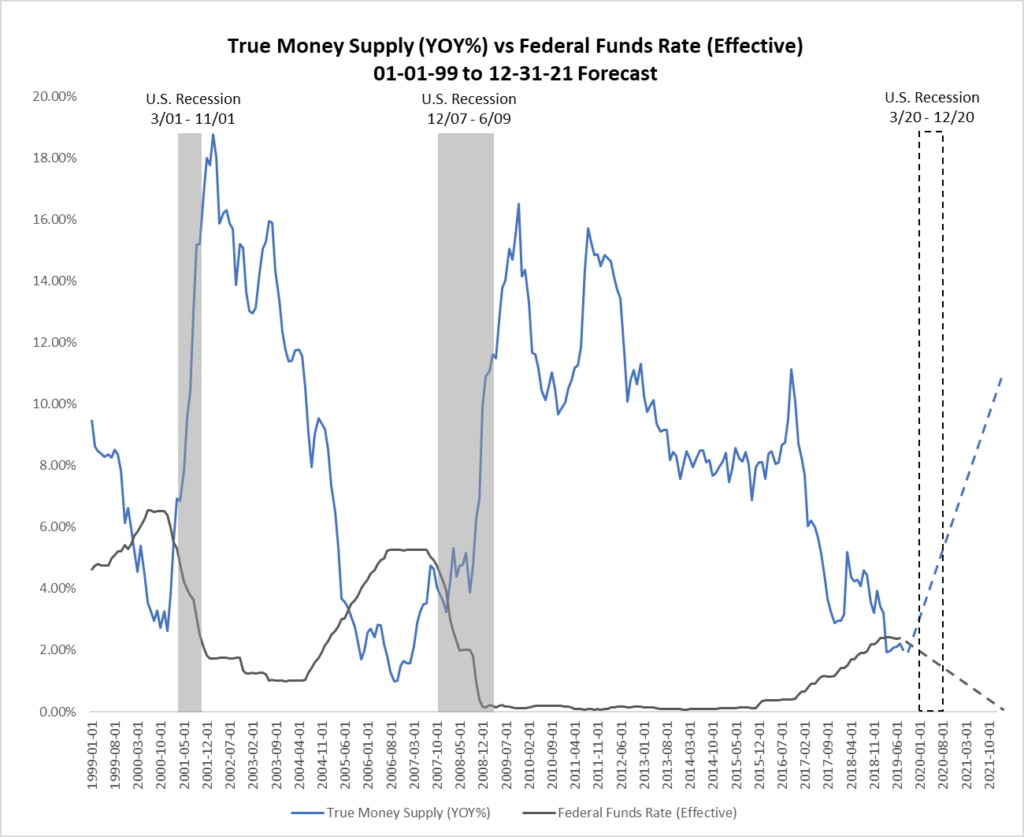

Therefore, the FOMC’s recent decision to lower the FFR by 25 basis points signals a shift in policy stance that will likely continue for the next few years. Shortly after the FOMC begins lowering the FFR, watch for the growth of TMS begin to accelerate. Then, as TMS begins to accelerate, expect the U.S. economy to fall into an economic recession. (See Figure 5.)

Figure 5: True Money Supply (YOY%) vs. Federal Funds Rate (Effective) 01-01-99 – 12-31-21 Forecast

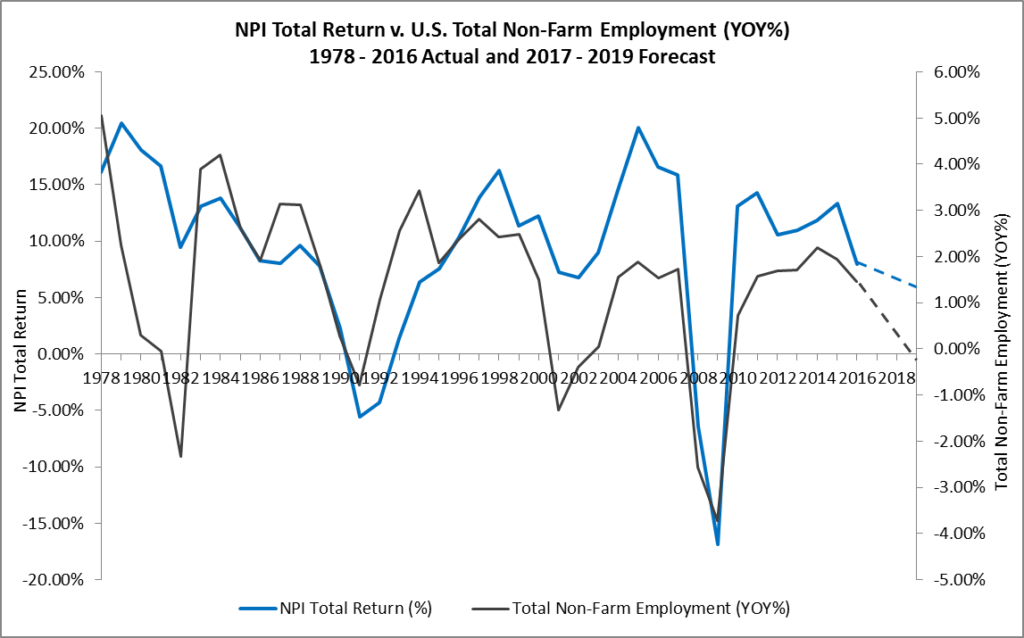

Recommended Investment Strategy

Because the next economic recession is still several months away, it’s not too late for real estate investors to take advantage of the still robust real estate capital markets to begin selling some of their under-performing and less-strategic assets and using the proceeds to reduce the leverage on their portfolios. By “dealing from the bottom of the deck” and reducing leverage, they will be improving the risk profile of their portfolios in anticipation of – and not in reaction to – the next recession.

Also, for the stronger performing and more-strategic assets, now is a good time to trade rate for occupancy, credit and term. Selectively approach existing credit tenants with a proposal to reduce their rent in exchange for an extended term. Similarly, reduce asking rates and increase concession packages for prospective credit tenants. By stabilizing occupancy with credit tenants and extending the weighted-average lease terms of the properties in their portfolios, investors will position their more-strategic assets to continue to perform well during the recession.

Conclusion

The TMS growth rate has leveled off at approximately 2% for the past six months and the FOMC recently lowered the FFR by 25 basis points. This suggests that the TMS growth rate has reached its low point for this cycle and that the next economic recession is not far off. In the meantime, real estate investors can make their portfolios more recession resistant by both selling under-performing and non-strategic assets before the recession and improving the risk profile of the rent rolls for the strategic assets that they will hold through the recession.

Thanks to Michael Pollaro for the TMS data used in this post.